Anant Welankar, a no nonsensical and tough police officer, and Jyotsna Gokhale, a romantic college professor, are having a good time at a posh Bombay restaurant in the early 80s. Even though Jyothsana protests his choice of such an expensive restaurant, for an important meeting that seems like their first date, Anant laughs it off and scrolls down the menu. Then, as a trigger to switch to the romantic side of the conversation, he flips through a poetry collection brought by Jyothsana and stuck with a particular poem. Attracted by the verses, he recites the poem loudly to her, “Before entering the circle of enemies/ who was I and how I was/ I didn’t remember it/… Whether I die or kill/ This will never be decided/ … On one hand is cowardice and other courage/ and at the center is the half-truth. His joyous face switches to a contemplative and somber one as he is repeating the lines eventually; he is trapped inside the poem.

The single shot scene moves on without any further mishap but already marks itself as one of the most poignant moments of Indian cinema. The movie was Ardh Satya, the 1983 cult classic, directed by ace cinematographer turned filmmaker Govind Nihalani. Ardh Satya was a milestone in many respects, predominant in them was the celebration of gritty textured cinema and raw characters, both in form and content. Ardh Satya stamped the cop subgenre of Indian cinema with an unseen intensity and authentic characterization and violated the good cop-bad cop dichotomy familiar to Bollywood enthusiasts till then.

The single shot scene moves on without any further mishap but already marks itself as one of the most poignant moments of Indian cinema. The movie was Ardh Satya, the 1983 cult classic, directed by ace cinematographer turned filmmaker Govind Nihalani. Ardh Satya was a milestone in many respects, predominant in them was the celebration of gritty textured cinema and raw characters, both in form and content. Ardh Satya stamped the cop subgenre of Indian cinema with an unseen intensity and authentic characterization and violated the good cop-bad cop dichotomy familiar to Bollywood enthusiasts till then.

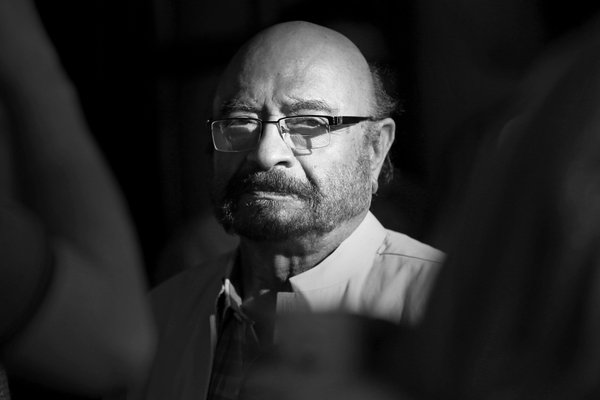

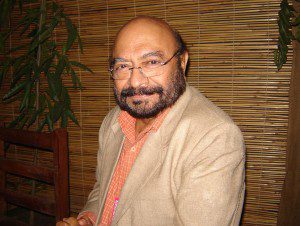

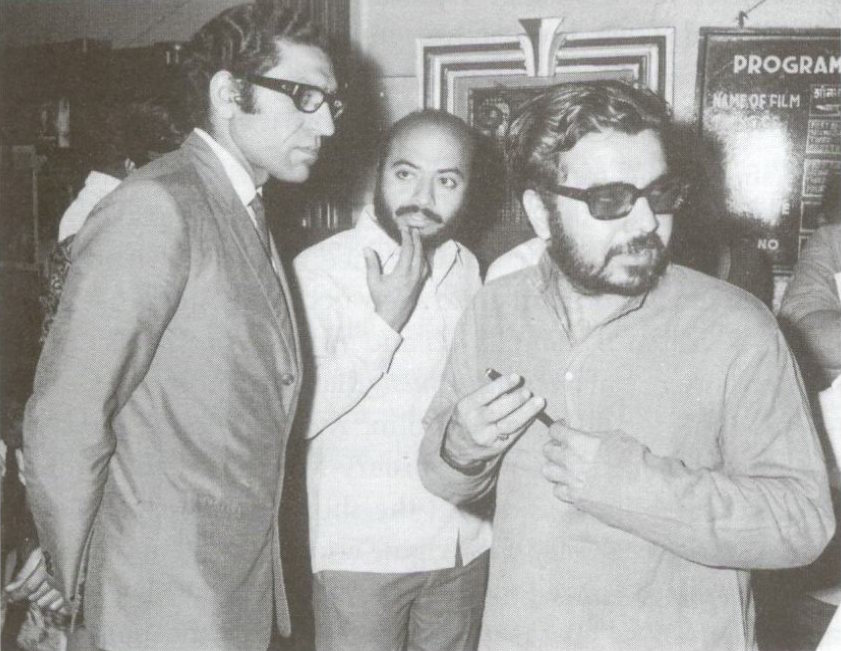

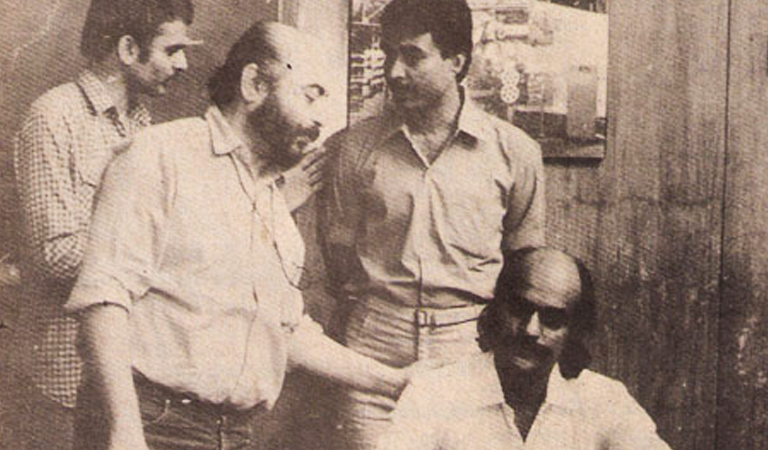

Govind Nihalani was born in Karachi, undivided India, and his family shifted to India after partition and independence of India and Pakistan. He graduated from the S J Polytechnic, Bangalore and landed in Bombay of the 70s, a time when the Hindi film industry was frequently bombarded by parallel cinema’s second wave crusaders like Shyam Benegal, Mani Kaul, Saeed Mirza, Kumar Shahani, and MS Sathyu. Drawing inspiration from regional cinema, Hindi cinema was opening up the gates and Govind Nihalani was in the right place at the right time. New frontiers were opened up for filmmakers, both in aesthetic and industrial terms, and they turned up with movies demanding a newer kind of viewing and understanding. After a prolific decade as a cinematographer in the 70s in Shyam Benegal’s films like Ankur, Nishant, Manthan, and Junoon, and an enchanting experience of making a documentary on auteur Satyajit Ray, Nihalani ventured into his directorial debut, Akrosh in 1980.

Mani Kaul; Interludes Of A Wind Chime And An Invisible Man

He started making his debut feature with a shoestring budget and a 16 mm camera. The movie was set in rural Nagpur with a burning theme of a protest of the tribal community against the oppressive and exploiting system. Akrosh also brought together Om Puri, Smita Patil, Naseeruddin Shah, and Amrish Puri under Nihalani’s umbrella and together they delivered some of the best works in the history of Indian parallel cinema in the years followed. Meanwhile, Nihalani nurtured a mentor-protégée relationship with legendary cinematographer VK Murthy. Nihalani revealed later that the lessons of framing and compositions he learned during those days as an assistant with VK Murthy helped him in a great deal while making movies as a director. In the 1982 movie, Vijeta, Nihalani showed the innards of the life of a young fighter pilot and the film hailed for its urgency and over the top visuals. It is also considered as a tribute to the Indian Air force for its original portrayal of air force men’s lives. In the meantime, Nihalani also worked as a second unit director with Richard Attenborough for his biopic epic, Gandhi.

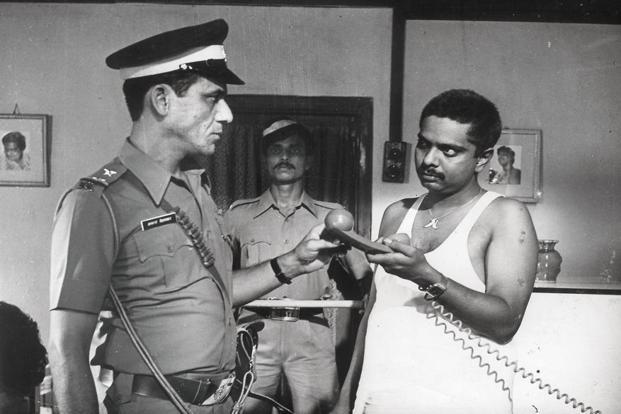

1983 saw Nihalani break through the conventional genre divide with his cult classic, Ardh Satya. The movie was an intense portrayal of the professional and personal lives of a sub-inspector of police, Anant Welankar, a performance of a lifetime by Om Puri, with his love interest Jyotsna Gokhale (Smita Patil) and rival gangster Rama Shetty (Sadashiv Amrapurkar) as other lead characters. Ardh Satya was Nihalani’s surgical take on human psyche under existential traumas in a hostile and corrupted system. The gritty shots and characters struck a chord with the viewers and the movie soon became a cult hit. After breaking through the commercial-art barrier of Bollywood through Ardh Satya, Nihalani came up with Party, a keen take on the double standards and intellectual pretensions of Indian middle and upper class, in 1984.

He lashed at the pseudo-intellectuals, hypocritical bourgeoisie society, and their meaningless ideological rhetoric through a group of party goers and Amrith, a young poet and tribal activist. In 1987, Nihalani took up the trauma and muddle of the partition with his 5-hour long television series, Tamas. He captured the confrontation at communal, political and personal planes from the viewpoint of the lead characters, Nathu and his pregnant wife, Kammo.

Hazaar Chaurasi Ki Maa, which came out in 1998, was an adaptation Mahasweta Devi‘s Novel, Hazaar Chaurasi Ki Maa and unfolded in the backdrop of politically turbulent Calcutta in 1970-72. The movie tried to capture the controversial Naxalbari Movement in the gray area, with all its political and personal shades. His 2004 movie, Dev was another adaptation based on Manjula Padmanabhan‘s story Harvest and traversed through the globalized urban lives and human bodies, which is territorialized by multi-national companies. Nihalani always kept his pace with the time and his eyes were sensitive to the changes and impacts on individuals. His other major works as director include Aaghat (1985), Dishti (1990), Pita (1991), Drohkaal (1994), Takshak (2000), and Dev (2004).

Even though Bollywood had its share of parallel cinema by the 70s, Nihalani introduced the vigor and explosive aesthetic of cinematic storytelling, transferring intense emotions through gritty and raw characters. Unlike some other parallel filmmakers, he never ignored the viewer’s sensibilities, which are shaped and conditioned by the Bollywood templates of romance, action, comedy, fear, and tragedy. Nihalani’s cinematic techniques were eager to hold the viewers close; a “The Battle of Algiers “like urgency enabled his visual language to keep a check on the characters’ emotional trajectories. His camera angles, movements and editing approach were formed in such a manner that no other filmmakers could capture and transferred what a character is going through to the audience.

This competitive edge in transmission loss was Nihalani’s characteristic trait and he picked up his themes and characters from the most diverse and violent strata of the society. They spoke an unpolished language and their genuine reactions were born out of a deep angst, desperation, and disillusionment. Most of them were seen traveling a downward spiral of mental breakdown, trying to retort and recuperate all the way down. But, he never let them down and they stood seasoned by the hostility and injustice, as unsure as for any individual in a volatile society bombarded and molded by contradictory forces. Govind Nihalani is the director of the fury of a fist, whose camera became violent whenever he turned it towards his central characters’ chaotic minds.

Written By: Ragesh Dipu