The 2001 Malayalam movie, Dany ends with a close shot of an epitaph that reads “Daniel Thompson, 1930 – 2000”, which painfully summarized the protagonist Dany’s life in minimal terms. The Realismo magico moment in the final shot unearthed when Dany’s tombstone seen erected in Bhargavi Amma’s place, a subplot consists of a late spring love story rolled out when an abandoned Dany met equally desperate Bhargavi Amma at an old age home, personal property. Being a member of a feudal, upper-class Hindu community, her decision to bury Dany, a Christian, in her place stirs quite a havoc among the neighbors. While tombstone and cross stand firm in a traditional Hindu household like a satirical statement about the ways society perceives and controls one-to-one human interactions based on religion, caste, and gender.

abandoned Dany met equally desperate Bhargavi Amma at an old age home, personal property. Being a member of a feudal, upper-class Hindu community, her decision to bury Dany, a Christian, in her place stirs quite a havoc among the neighbors. While tombstone and cross stand firm in a traditional Hindu household like a satirical statement about the ways society perceives and controls one-to-one human interactions based on religion, caste, and gender.

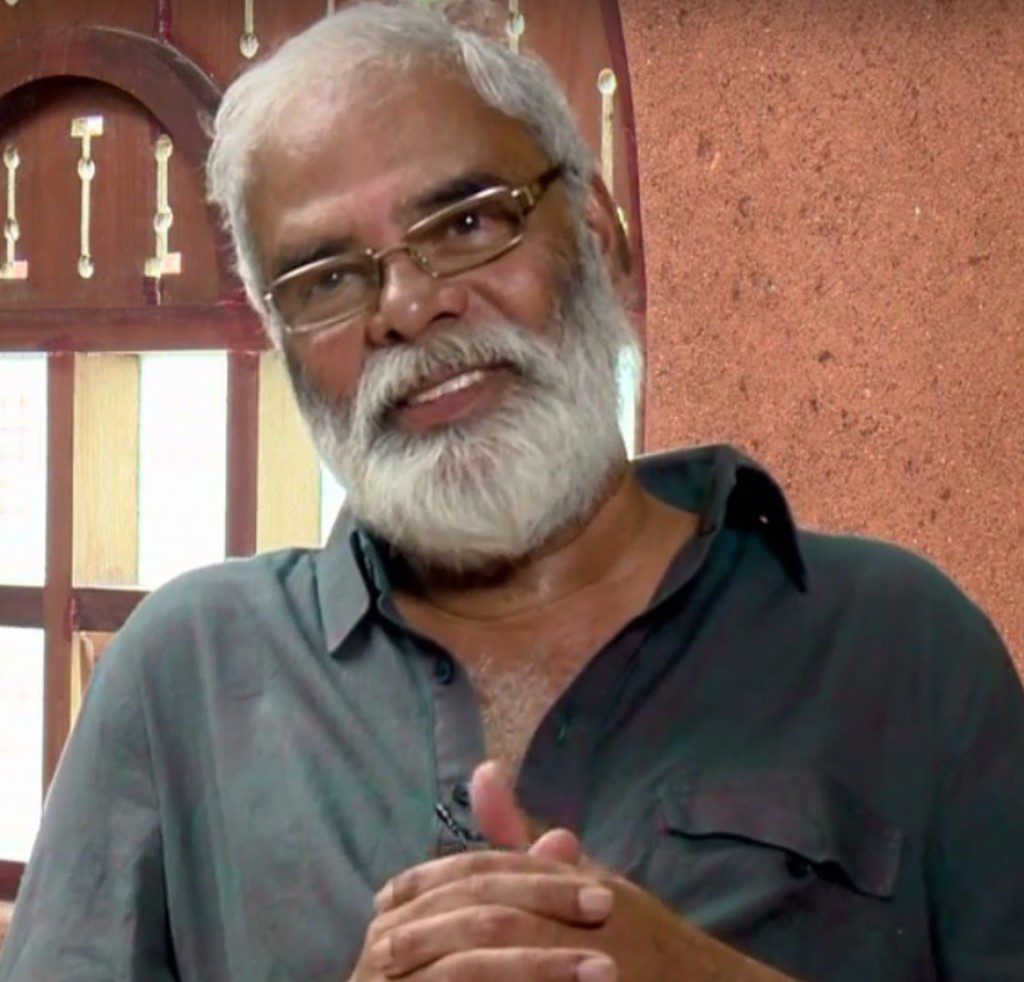

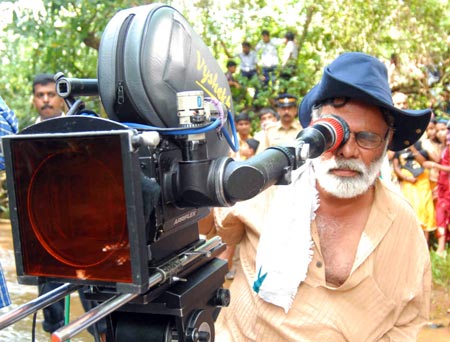

Upon this decisive last frame, the credits, written and directed by T.V. Chandran, start rolling up, and no other Indian filmmaker could imply the aesthetics of his political stand like Chandran, a prominent figure of the parallel stream of Malayalam cinema. His filmography is rich in content and counts with movies that touch almost all the facets of human existence, with the marginalized, displaced, and oppressed individuals get their unique expressions and representations. Along with other radical filmmakers like John Abraham, Pavithran, PT Kunjumuhammed, PA Backer, and KP Mohanan, TV Chandran has shaped the social-political-aesthetic front of Malayalam cinema from the late 70s, all through the prolific 80s and 90 and till late 2000s.

John Abraham, Portrait Of A Lucid Messiah

Born in Thalassery, a small colonial township in Northern Kerala, TV Chandran enrolled to the Reserve Bank of India as an employee after completing graduation and post-graduation. Chandran’s political views were influenced and shaped by the Naxalite movement prevalent in the late 60s and early 70s. No wonder he landed in the melting pot of the political turmoil of the Emergency as an actor through PA Backer’s daring take on state-sponsored violence, Kabani Nadi Chuvannappol (When the River Kabani Turned Red) in 1975. Even though the movie was crushed by the tyrannical censorship in those days and the makers PA Backer, producer VK Pavithran and Chandran had to go through Police brutality, the young Chandran discovered his flair for narratives of visual testimonials and started working as an assistant director with PA Backer and John Abraham, two of the most promising young filmmakers at that time.

A close friendship with the renowned avant-garde filmmaker VK Pavithran had also christened Chandran to put on the crown of thorns of a director. In those days, filmmaking was more like a group ritual in Kerala, with filmmakers established close ties with society and movies with radical outlook were coming out of collectives and radical groups, and a deep rooted Film Society movement ignited a new attitude of appreciation among movie buffs. T.V. Chandran and his contemporaries shrugged off the art for art sake modal and keen to incorporate the common people from all strata of the society into the process of filmmaking. The same people found the representation of their persona in these filmmakers’ characters and identified their struggles with the central themes in these movies.

Govind Nihalani – Fury Of A Fist And A Violent Movie Camera

T.V. Chandran started his filmmaking career from the PA Backer school, carrying forward many of his thematic and formal preferences through the 1981 directorial debut, Krshnankutty. The movie failed to impress critics and viewers alike but put forward a new style initiating dialogue between individual and society and ideology and pragmatism, a personalized style Chandran sharpened in his next flicks. In 1985 he returned to the director’s chair with a Tamil flick, Hemavin Kathalarkal (Hema’s Lovers), which was a proletariat saga based on the labor unions. The movie earned him first recognition as a promising young filmmaker. The movie also sowed the seeds of Chandran’s leftist ideological preferences, an unwavering stand he has been keeping for a career spanning more than 35 years.

Chandran plunged into his realm of underprivileged and destitute with his third venture, a Malayalam movie Alicinte Anveshanam (The Search of Alice), in 1989. The movie paints a portrait of a desperate housewife searching for her disappeared husband in sharp strokes. Alice was the first iconic female character Chandran created among many others in his oeuvre, and soon became an archetype for wandering, either physically or emotionally, women who discover their true self at some point of this quest for identity, threatened and bent all the way by a rigid and hostile patriarchal framework. Alice also brought the first international recognition for Chandran when it was nominated for the Golden Leopard at Locarno International Film Festival in 1990.

In 1993, Chandran turned up with Ponthanmada, which is considered as his magnum opus by many critics, and depicted the body-politics through an intense brotherhood developed between two men, the low-caste Ponthan Mada and his colonial landlord Sheema Thampuran, in the 40s of rural Kerala. The movie established Chandran as a prominent figure in the Indian independent cinema movement and bagged a number of awards, including the National Film Award for Best Director, for him. Ormakalundayirikkanam (Memories and Desires) happened in 1995 and Chandran pushed his boundaries as an independent filmmaker further by commenting on the historical events surrounding the dismissal of the first democratically elected Communist government in Kerala in 1959 through the eyes of a boy. In the 1997 movie, Mangamma, Chandran followed Mangamma, a desperate woman who went through constant harassment at various epochs of history by respective patriarchal agents prevalent at that time. Being a sterling portrayal the trauma and struggle the womanhood undergoes under patriarchal structures of a nation, society, and family, Mangamma is one of the landmark movies of Indian feminist cinema.

He attempted to solve the complex gender-based power equations in his 2000 movie, Susanna. The movie was an audacious take on feminine identity when Chandran’s protagonist forced to share her body with five older men and eventually became their only solace at the eve of their lives, daring stringent remarks and gazes from the familial and societal orthodoxy. Dany, which is considered as a masterpiece by many critics, came out in 2001 and dealt with the destiny of a desperately muted protagonist, who is sidelined by the mainstream historic narrative and at the same time, witnessed many of the epochs as an irrelevant observer. Dany can be considered as the most personalized narrative of Chandran with its stark portrayal of a helpless individual against the merciless power fields of meta-narratives like social and family history. With the 2003 movie, Padam Onnu: Oru Vilapam (Lesson One: A Wail), Chandran shifted his focus from personal cinematic narratives to burning social issues and his protagonists stood either as victims or mirrors of social injustices.

Resul Pookutty & The Essentials Of Indian Sound Effects In World Cinema

He continued to explore the plight of the invisible and the irrelevant in his subsequent movies, Kathavasheshan (The Deceased, 2004), Aadum Koothu (2005), Vilapangalkkappuram (Beyond the Wail, 2008), Boomi Malayalam (The Mother Earth, 2008), Sankaranum Mohananum (Sankaran and Mohanan, 2011), Bhoomiyude Avakashikal (The Inheritors of the Earth, 2012), and Mohavalayam (2016). The recurring motif of Chandran’s movies is the quest of the invisible or obscured protagonist for identity or meaning in their life. Chandran empathetically follows this quest and subsequent trauma and struggle against a backdrop of narratives like history, whose allegiance always lies with the dominant ideologies like patriarchy, fascism, misogyny, religion, caste, and class. His themes are flavored with a clear standpoint of Marxian ideology and his narrative interacts with the historical process according to Marxist dictum.

T.V. Chandran belongs to the rare group of Indian filmmakers whose unique thematic explorations always accompany with equally competent formal experiments. As a filmmaker, Chandran allows his characters to dream; a privilege restricted to them in their real life and initiates the viewers to take part in those dreams. Thus, his movies create a specific dreamy zone of mutual interaction between the characters and viewers, where both come to know each other inside out and nothing left classified. The filmmaker starts from the basic unit, the individual, and gradually elaborate his perspective into a societal canvas and makes it wider by placing it against a vast historic plane, with questioning and provoking the existing norms of various systems. Female characters gain a lot from this approach and almost all of his women protagonists voice questions regarding identity and self-determination, which were suppressed hitherto. Naturally, almost all of his male characters are either dwarfed or inferior to their female counterparts and succumb to this trial of historic interrogation. T.V. Chandran positions his body of work in the controversial realm of the invisible and obscured identities, which are muted or suppressed by the so-called mainstream narratives.

Written By: Ragesh Dipu