Every art form has certain parameters that make it essentially an art, and when it comes to cinema, these elements are always on a slippery platform. The question, what are the key elements that make cinema an art, bears different answers at different spaces and time. And, nowadays the prevalent answer shifts towards the filmmaking technology and often, the filmmaker is glorified for his status as a technological wizard. Very few people touch the issue of mastery in cinematic language and its masterly displays through the craft.

answers at different spaces and time. And, nowadays the prevalent answer shifts towards the filmmaking technology and often, the filmmaker is glorified for his status as a technological wizard. Very few people touch the issue of mastery in cinematic language and its masterly displays through the craft.

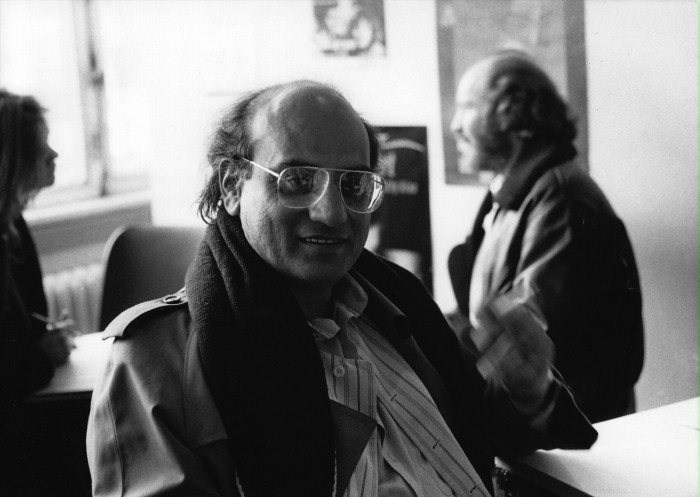

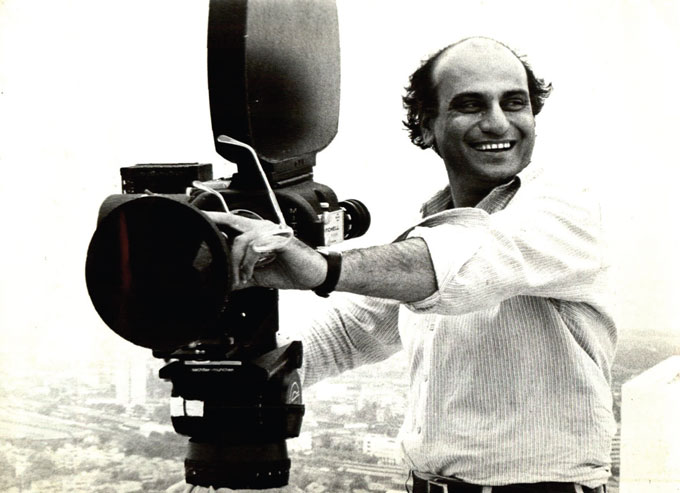

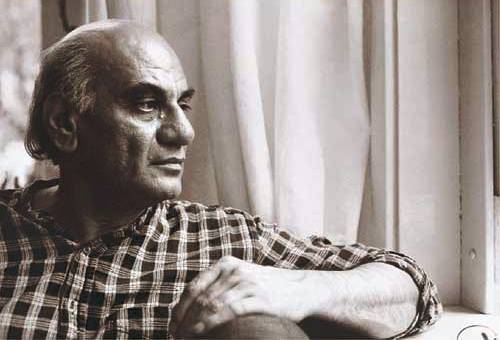

“If film shows you something you already know, where will it lead us?” maverick Indian filmmaker Mani Kaul asked once. Let’s push aside the possible answers because the question here, is a key to unlock the master filmmaker’s oeuvre, which is labeled as too formal, mystical, dull, and western in India and, on the contrary, too regional, rooted, impenetrable, and metaphysical in the West. The rhetoric surrounding Mani Kaul and his movies was always debatable, and for critics who, instead of exploring the filmmaker’s craft by penetrating his form, settled on tagging his movies as metaphysical, mystical and experimental.

But, they missed a delicate chord connecting his internal eye, which is organic and intuitive, and his unique image making, and that blind spot of the critics made directors like Mani Kaul invisible in the history of Indian cinema. Kaul’s cinematic journey traced back to the very notions of beauty and its evolution through history. Through his journey, Kaul drew a map that put forward a new aesthetic that locked horns with all the conventional aesthetic approaches in the East and the West.

John Abraham, Portrait Of A Lucid Messiah

Mani Kaul was born into a Kashmiri family in Jodhpur, Rajasthan. His maternal uncle Mahesh Kaul was an actor-director and made movies like Sapnon Ka Saudagar in Bollywood, and can be considered as the first envoy sent by cinema to meet the little Kaul. The “see it and transform” mode of filmmaking evident in Kaul’s works has its origin in this childhood. As a young boy, Kaul was suffering from acute myopia and couldn’t see more of the world as it was. The boy thought this was quite natural until his father noticed this difficulty during one excursion and fixed the problem with a pair of glasses. For a few days after getting the glasses, Kaul was hyper active to wake up early in the morning to see his city slowly awakening from the morning sluggishness and the shadow play of light on the streets.

In the mid-60s, Kaul enrolled in the Film and Television Institute of India, FTII, as an acting student. But, he couldn’t resist the call of his inner eye and soon transferred himself into the direction course. Kaul’s diploma film, Shraddha, a short, depicting a man’s desperate effects to patch up with his quarrelling wife, set his footing firm on the filmmaking ground with all his signature traits like mastery in converting the visual conceived in his inner eye into the language of the lens, and using the cinematic space with affirmation. FTII paved seeds of Kaul’s preoccupations with painter Paul Cezanne’s “there is no corner of a painting” approach with microscopic detailing of objects, Ritwik Ghatak’s affinity with classical Indian aesthetic, music and Mughal miniature paintings, Robert Bresson’s idea of the juxtaposition of shots, and Matisse’s deliberately disorientating and unsettling color pattern to create an experience of balance, purity and serenity.

The Cloud Capped Star, Glimpses Of Ritwik Ghatak’s Cinema

After passing out from the Institute, Mani Kaul made his first feature, Uski Roti in 1969. The Haunting image the lonely housewife, waiting for her husband underneath a tree on the highway with a Roti carrier made of cloth, became a symbol of the Indian art cinema the 70s. Uski Roti announced Mani Kaul’s provoking and innovative form-content equations and along with the legendary cinematographer K.K. Mahajan, Kaul achieved all he wanted through the emotionally unsettling closeups of his lead actress using a wide angle lens. The movie was a labyrinth of silence that pierced occasionally by very few dialogues. Kaul’s love for sad human faces and expressive landscapes came into age through Uski Roti and the movie divided its viewers and the critics into two because of its stark departure from conventional narrative and treatment.

He turned up again in 1971 with the movie Ashadh Ka Ek Din, which was an adaptation of the Mohan Rakesh’s play of the same name. Mani Kaul continued to explore the silent trauma of suffering leading ladies in Ashadh Ka Ek Din and the movie went on to win Filmfare Critics Award for Best Movie of the year.

In 1973, Kaul made Duvidha, which is considered as his most acclaimed work by many critics. In Duvidha, Kaul went so far as to make his lead female actor, wearing a red saree, standing against a white wall, staring sharply into the viewer,with piercing Rajasthani folk music filling the background. Duvidha dealt with the ghost who falls in love with a newly married woman and inhabited in her body. With the help of jump cuts and recurring visuals Kaul controlled cinematic time like a musical instrument and devised a highly personal aesthetic painted with red and white palette. He employed a narrator to explain the story so that he can relieve the actual visual narrative of the burden of storytelling. The past, present and future of the bride entangled in a complex way to thrash linear perception of the viewer. With Duvidha, Mani Kaul established as a significant figure in the Indian art film scenario.

After some commissioned documentary projects, Kaul returned to feature films with Satah Se Uthata Aadmi in 1980. Based on the autobiographical notes of Gajanan Mukthibodh, Satah Se Uthata Aadmi revolved around a poet who resides in godforsaken house, detached himself from the realities of daily life. With the help of a voice over that interconnects the visual narrative, Kaul draws a fragmented picture of a world where philistine powers took over art, revolution, ideals and humanity.

Mani Kaul returned to his favorite realm of classical music with his 1982 documentary, Drupad. He explored the oral traditions of Drupad, a Dagarvani derivative of the Indian classical music of the Dagar family. Drupad was a path breaking achievement in experimenting with cinematic time and documenting the historical significance of an oral tradition. Kaul effectively pulled together the thread of Indian music, sculpture, architecture, painting, and cinema into a single but fragmented narrative.

Kumar Shahani, A Forgotten God And A Misplaced Image

The year 1989 witnessed one of the boldest attempts in the history of Indian documentaries when Mani Kaul endeavored to document the life and music of Siddheshwari Devi, a popular classical singer from Varanasi. The movie, Siddheshwari, avoided almost all the biographical detailing, a convention in biographical documentaries, and elevated the viewers into a higher level of understanding of the singer’s persona and art. Kaul exorbitantly used multiple timelines, role plays, voice overs, poetry, monologues, and various ragas, all pull together by a table of contents scroll up unexpectedly at the beginning of the movie.

From his Institute days, Mani Kaul had been conscious about the possibilities of form in cinematic expression, to carry over or generate the connections with viewers’ consciousness. And, he synthesized all the other Indian artistic form like literature, painting, architecture, poetry, and music in his peculiar form-content framework. For this, he began with images and then explored more and more into it. He drew a lot of inspiration from the Indian classical music and preferred to edit his movies like a musician composing music. Like Matisse, he believed in discovering an already existing, but hidden, form for his movies, instead of creating one. He worked tirelessly and intuitively till the right shot falls in the right place to generate the right rhythm.

From his Institute days, Mani Kaul had been conscious about the possibilities of form in cinematic expression, to carry over or generate the connections with viewers’ consciousness. And, he synthesized all the other Indian artistic form like literature, painting, architecture, poetry, and music in his peculiar form-content framework. For this, he began with images and then explored more and more into it. He drew a lot of inspiration from the Indian classical music and preferred to edit his movies like a musician composing music. Like Matisse, he believed in discovering an already existing, but hidden, form for his movies, instead of creating one. He worked tirelessly and intuitively till the right shot falls in the right place to generate the right rhythm.

Fragmentation and detachment are the two recurring motifs in Kaul’s filmography. He preferred closeups of hands, legs, fingers, head, and other parts of the body as much as the artist’s face. In order to shed the three dimensional depth of images, Kaul went for flat cinematography and his characters wander through meditative landscapes without any hold on their destiny. Kaul also devised a slow camera movement to compliment this feeling of aloofness.

Major works of Mani Kaul include, Uski Roti (1969), Ashadh Ka Ek Din (1971), Duvidha (1973), Ghashiram Kotwal (1979), Arrival (Documentary, 1980), Satah Se Uthata Admi (1980), Dhrupad (1982), Mati Manas (Documentary, 1984), Siddheshwari (Documentary) (1989), Nazar (1991), Idiot (1992), The Cloud Door (1995), and Naukar Ki Kameez (1999).

“The basic problem arises in not being able to relate to a work which does not have, first, a centre and, then, a structure. A structure enables you to relate to the whole meaning. If I make something in clay, I take some wire and create a rough structure of the figure and then I start putting some clay around those pliable wires and this structure is not just holding the clay or giving it form but also guiding it. It also makes you relate to the whole immediately; you have an idea of what the posture is like. It gives you a contact with the “whole”. Imagine what kind of films I make, when I don’t have a centre, or a structure of which I am not certain. What I want to relate to is the idea of uncertainty – crucial for me is the “uncertain”. There is a possibility that the audience will not understand, but the most unfortunate thing is that there is not even a curiosity to understand, which is a tragedy,” Mani Kaul once remarked in a conversation.

That is the tragedy, we need to address in order reinvent the invisible man of Indian art cinema. And, the footnote reads that, Mani Kaul had to shift his focus into teaching cinema and classical music by the end of his career, as it was difficult to fund his movies. Mani Kaul passed away on 6 July 2011, leaving behind the interludes of a wind chime, and his movies end only physically, while his images lead other lives even after the end of the movie.

Written By: Ragesh Dipu

Main Image Courtesy: berlinale.de