When the Hindi movie, Maya Darpan, featuring relatively unknown cast and made by a newbie filmmaker, managed to have a

limited release in 1972, the responses were diverse, ranging from lukewarm to hostile. The majority of the critics brushed the movie away, incriminating a languorous pace and non-Indian sensibility. The viewers too had missed the movie due to its limited release and flood of negative reviews. The movie, Maya Darpan was forgotten mercilessly in the following years, to an extent of losing the original negative of the movie. Nevertheless, the ill-fate of his debut feature met with in his homeland never discouraged its director Kumar Shahani, and he went on to make movies that put forward a unique aesthetic and sensibility.

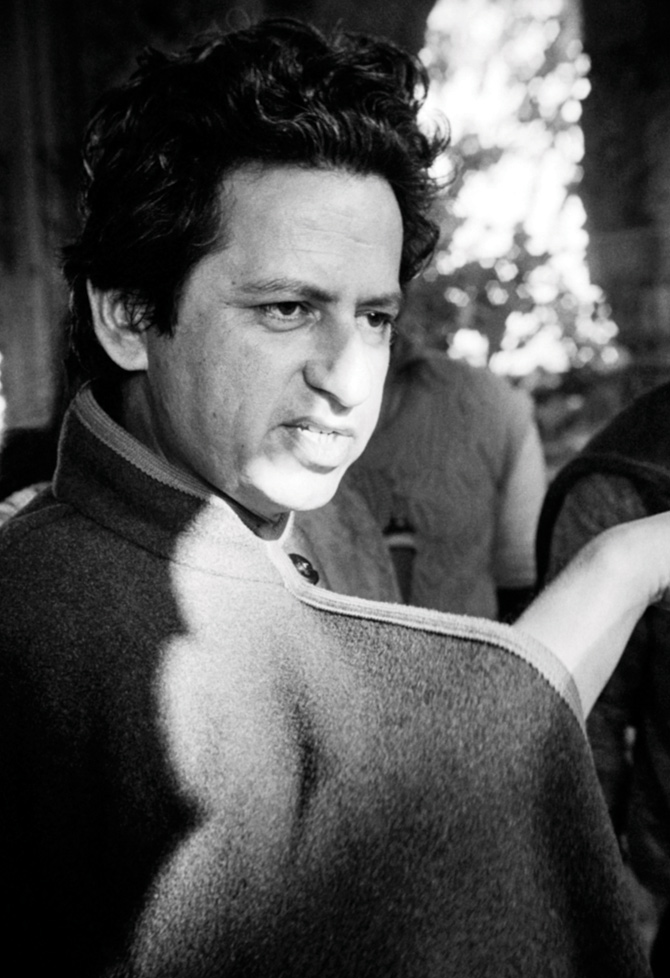

Kumar Shahani, who born in the undivided India, migrated with his family to settle in Mumbai after independence. Even though graduated in Political Science and History, Shahani landed in the Screenplay writing and advanced direction course in Film and Television Institute of India, Pune. There he met his first mentor, Ritwik Ghatak, who was teaching there at that time. Shahani’s FTII days with Ghatak made indelible marks on his perspective and style. After a short stint of research under renowned historian DD Kosambi, Shahani flew to France to study at the Institute des Hautes études cinématographiques (IDHEC), where he discovered his second mentor, Robert Bresson.

The Cloud Capped Star, Glimpses Of Ritwik Ghatak’s Cinema

Shahani worked with Bresson in the movie Une Femme Douce and sharpened his unique aesthetic preferences during the French interim. He witnessed and experienced the turbulent Paris during the 1968 student uprising and took the rebelling students slogan “Let imagination take over power” to his heart. Shahani kept an artistic detachment with the burning nucleus of the uprising and at the same time, internalized the ongoing chaos of creative energy. Shahani left France for India with refreshed perceptions of politics in art and art in politics. He was all set to take a shot at his sharpened form-content equations, on the culturalscape of his homeland.

Maya Darpan, Shahani’s debut feature happened in 1972. The movie microscopically analyzed female sexuality in the backdrop of belittling, but oppressive feudal forces and a thriving and ambitious industrial scenario. Maya Darpan marked the coming of age of Indian parallel cinema and is considered as a milestone movie in the history of Indian Cinema. Kumar Shahani used a brilliant color palette to portray Tarun, the younger daughter of a Rajasthani zamindar and her struggle, both in the psychological and physical terrains, against patriarchal society and its moral norms. Shahani maintained a Bressonian formalist approach that is refined with an ingenious Indianness throughout the movie. One can also find Shahani’s immaculate and characteristic rhythm in Maya Darpan.

After a dismal reception and oblivion of Maya Darpan that cost him a long creative gap of 12 years, Shahani reinvented himself with the movie Tarang in 1984. The movie was marked by the elaborately complex detailing of the epic forms of storytelling in an Indian context. Shahani explored the creating, protecting and killing archetype of the mother goddess in a modern backdrop through his lead female characters Janki and Hansa. He was retrieving the oral tradition of folklore, which holds the epic form narrative in its heart. By including a number of Bollywood-style songs, Shahani showed how such traditions are surviving in popular art, but in a distorted form.

After 5 years, in 1989, Shahani returned with Khayal Gatha, an amazingly abstract attempt to explore the history of the vocal genre, Khayal, of Indian classical singing. The movie traced a music student’s footprints to discover stories and legends about the Khayal genre and its aesthetic bindings with Indian classical dance forms. Khayal Gatha brought Shahani his first international recognition and the movie was hailed for its lyrical beauty and rhythm.

In his 1990 movie Kasba, Shahani chose a short story by Anton Chekov to make it into a gripping philosophical tale of the psychological and emotional labyrinths of the characters. The movie encompassed layered meanings, which were executed through particular camera angles and frame compositions. Shahani’s rigorous use of narrative ellipses made Kasba a hard nut to crack and the viewers had to closely follow the characters and individual pieces to form a coherent viewing experience of the movie. The clash of feudal patriarchy and modernity is presented through the character of Tejo, a young woman who runs the family business in the absence of two sons of the family.

Shahani’s 1997 movie Char Adhyay was adapted from Rabindranath Tagore’s novel of the same name and dealt with the ugly turnouts of nationalism. Shahani wove a complex net of glorified nationalism and choking idealism through a group of

youngsters in the backdrop of the Bengali Renaissance of the 1930s and 1940s. Once again, at the epicenter of Shahani’s narrative structure was a woman and he showed repressed desires clash with a unilateral commitment to a cause and the subsequent collapse of individual integrity. Shahani adapted a formalist approach of overlapping the past with the present and the beauty with the mystery in the movie.

Most of his movies are characterized by a slow pace to the point of stillness. Shahani often criticized ruthlessly for this stillness of his moving images, which achieved through choreographing the actors according to his internal rhythm. But, the same accusations made him an irresistible auteur in Indian cinema. Shahani always stood firm on the stand that the content emerges through the way an artist related himself to his object. To him, the visual beauty of a movie was deeply connected to the editing, the rhythm, the shot taking, the pattern of movement, and the sound and a combined effect of all of them constituted the content in his movies.

His major works are Maya Darpan (1972), Tarang (1984), Khayal Gatha (1989), Kasba (1990), and Char Adhyay (1997). He had also made a documentary film on Guru Kelucharan Mahapatra, the legendary Oddissi dancer, in Oriya named Bhavantarana.

The Silent Sculpture, Govindan Aravindan’s Universe Of Cinema

Ever since Shahani interacted with Kosambi and Ritwik Ghatak, he was deeply influenced by the Marxist aesthetic and epic structures of narratives. But, he was always critical of working adherent to any structure and believed that a tradition grows through criticism. Shahani belongs to a rare fraction of Indian filmmakers who tried to invent a new language in filmmaking by understanding the tradition and initiating a dynamic shift from that tradition. Unfortunately, Indian critics and audiences couldn’t acknowledge that initiations and some of the real gems of Indian cinema are facing oblivion.

Written By: Ragesh Dipu

Main Image Courtesy- www.upperstall.com