When the cartoon series titled Cheriya Manushyarum Valiya Lokavum (Small People, Big World) appeared as a surprise for many of the readers of Mathrubhumi, a leading illustrative weekly in Malayalam in the Kerala, in the early 60s, it was subtle beginning like his movies. But soon, the individual pieces of the cartoon strip gathered momentum by gathering a cohesive narrative that incorporated representative characters and interpreted the socio-political scenario of Kerala at that time. With some minimal brush strokes and ironic texts, the series lured followers and the lead characters, Ramu and Guruji, became familiar names in the cultural sphere of Kerala. That’s how the maverick filmmaker, G Aravindan announced the emergence of a new way of seeing things that characterised with a contemplative pace, minimal details and a poignant approach to themes and characters.

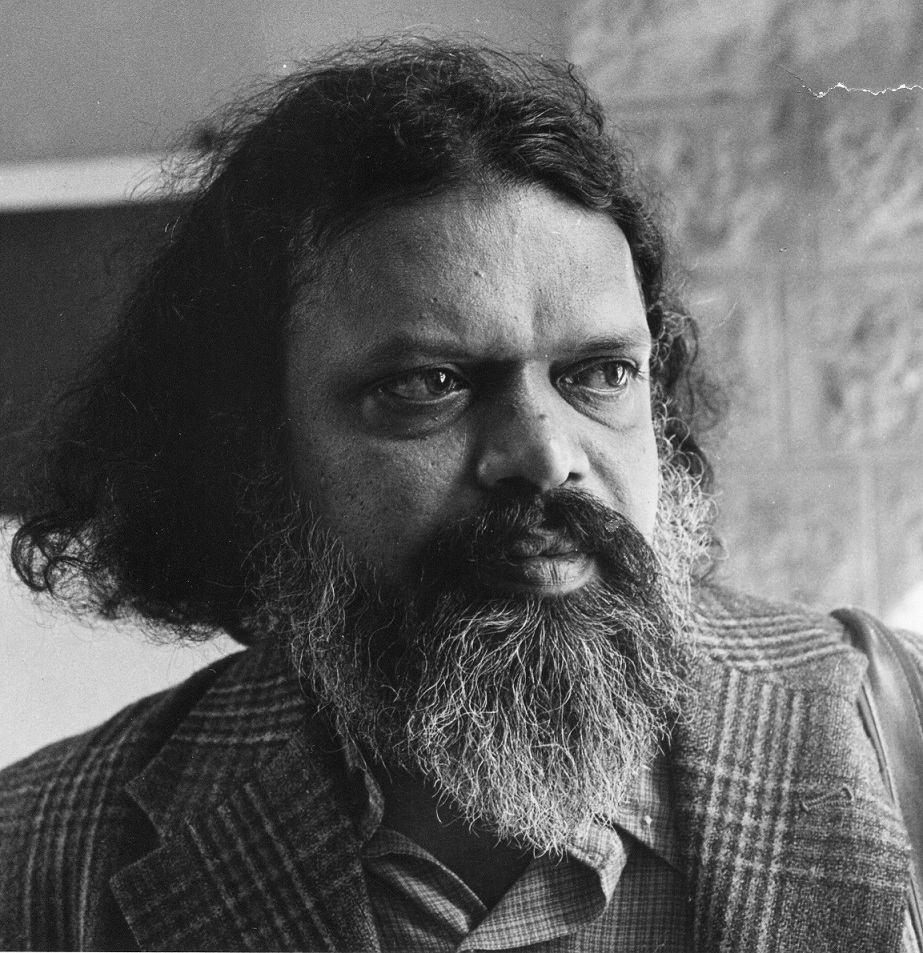

The key to unlocking G Aravindan’s universe of artistic endeavours is the title “Cheriya Manushyarum Valiya Lokavum (Small People, Big World). It holds the essence of his artistic vision, which viewed and interpreted the singled out the individual against a backdrop of imposing and the gigantic outer world. This microscopic treatment of his subjects in the backdrop of macroscopic systems enables Aravindan to dig out the conflicts between individual and well-organised systems like family, society, religion and state. All his characters are small beings, attributing their smallness as a mark of their identity. When Aravindan turned his camera towards them, he looked for the spiritual light ignited inside these individuals who made Lilliputians by imposing power structures around them.

The Cloud Capped Star, Glimpses Of Ritwik Ghatak’s Cinema

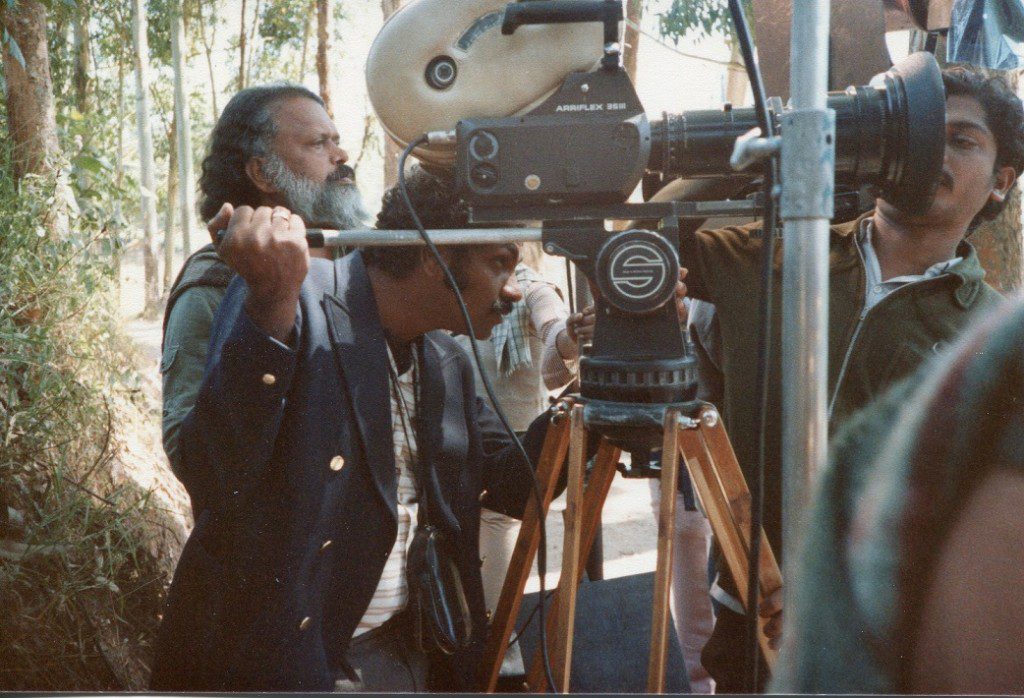

Aravindan entered the cultural scenario of Kerala in the 60s, an era marked with the prominence of modernist artists. Joining hands with Kavalam Narayana Panicker, the pioneer of indigenous theatre in the state, Aravindan rendered some landmark plays. His ideas of mise en scene and sensitive use of space found roots and his resonant visual narrative started to evolve during this stint with theatre. In 1974, Aravindan ventured into filmmaking as Kerala underwent through a revolution of film society movement and getting receptive to art house cinema, mostly because of a crusade led by renowned filmmaker Adoor Gopalakrishnan. The soil was ready and open to Aravindan to land with his debut feature Utharayanam.

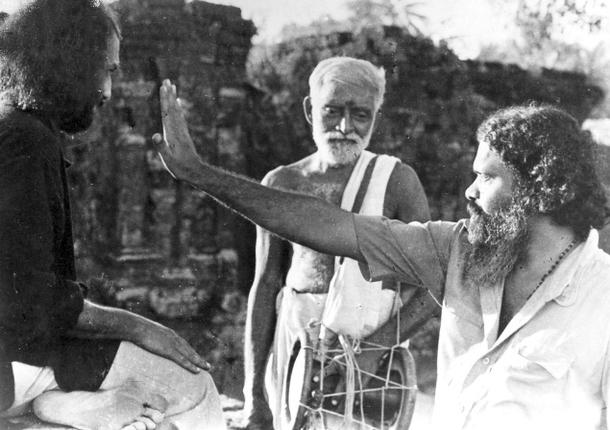

Utharayanam dealt with the disillusionment of a nationalistic spirit and euphoria among youth after independence and won critical acclaim. After Utharayanam, Aravindan moved on to more ambitious attempts with his Kanchanasita in 1977, a daring and never-seen-before experimental movie, which presented the important characters in the epic Ramayana as vulnerable persons, striped of all godly aura. Aravindan chooses members of a tribal community in Andhra Pradesh to play Ram and Laxman, a rebellious and political move to portray the humanity hidden in their godliness. Moreover, he realised Sita as nature and made her presence felt all over the movie with the help of natural elements like wind.

Kanchanasita enabled Aravindan to approach filmmaking with more confidence as he shifted his realm into the realistic narrative and “Thampu” happened in 1978. The movie revolved around a travelling circus group and the stagnant village they camped. It was followed by “Kummatty”, a children’s movie and Aravindan returned to his favourite terrain of myths after that. “Esthappan”, which dealt with how a mysterious vagabond elated as a mythical figure and presented through a series of testimonies, was one of the first of its kind in Indian cinema. Aravindan lavishly used magical realism throughout the movie to connect and distinguish the protagonist Esthappan’s world with the common man’s. The movie stood out as a rare gem that connected Indian cinema with oral traditions prevalent in the country.

In his 1985 movie Chidambaram, Aravindan dived into the abyss of moral conflicts and the movie marked one of the best on-screen performances by the lead pair, Bharath Gopi and Smita Patil. Aravindan dissected the fortress of morality with surgical precision. From the personal realm of Chidambaram, he returned to documentary realism in his next film “Oridathu”, which discussed the effects of development on individual and society.

Aravindan again experimented with form as his next work, “Marattam” effectively applied story-within-the-story narrative. His last feature film Vasthuhara crossed the borders and chronicled the miseries of refugees from Bangladesh after partition, in the viewpoint of a man who is torn between various power structures. Apart from the 15 feature films, Aravindan also made several documentaries including, The Seer who Walks Alone on philosopher J Krishnamurthy, Contours of Linear Rhythm on artist Namboothiri, Anadidhara on Indian folk art forms, and Sahaja on the concept of Ardha-Nariswara.

A look at Aravindan’s filmography makes it clear that the director was never set allegiances with any particular style, form or genre. All his works were a search for the meaning of cinema itself. Being an autodidact, Aravindan was always eager to try new things and push the boundaries of cinema as a medium. In his 1981 movie, “Pokkuveyil”, Aravindan recorded the background score by Hari Prasad Chaurasia beforehand and canned visuals according to the soulful rendition of Chourasia’s flute.

The empathetic and detached approach of Aravindan made his movies unique and they grow inside the viewers over the course of time. He was often indifferent to using closeups and always keen to present his subject connected to his or her surroundings. Aravindan also had a deep knowledge of Hindustani music and used music very effectively to compliment various moods . He had also worked as a music director for other filmmakers’ movies like Yaro Oral, Piravi and Ore Thooval Pakshikal.

Aravindan’s major movies are Uttarayanam (1974), Kanchana Sita (1977), Thampu (1978), Kummatty (1979), Esthappan (1980), Pokkuveyil (1981), Chidambaram (1985), Oridathu (1986), Marattam (1988), Unni (1988), and Vasthuhara (1991).

“It’s Like A Stone In Your Shoe,” Lars Von Trier On Filmmaking

Unlike other filmmakers in India, Aravindan was the most whimsical one and all his choices were originated from a sensibility that deeply rooted in regional culture, society, politics and myths. At the same time, he transgressed the regional barriers by seeing and presenting things with a third eye, which was quite universal. Aravindan took a path in cinema that had taken by a few filmmakers like Andrei Tarkovsky in world cinema and Mani Kaul in India.

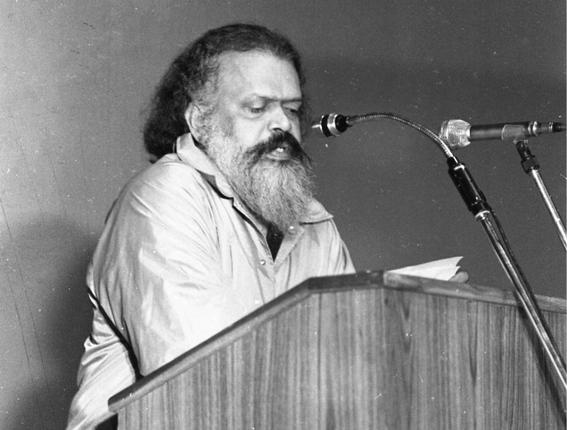

When asked about his filmmaking style, Aravindan once replied, “Mine is not a conscious effort. I very much like people who make departures from the mainstream people who are critical of the dominant way of thinking, taste, and habits. I try listening to them to understand their flight from reality. Some of them make some kind of a departure from the mainstream, but keep an active link with it. Some make the departures and live it out – the yet to be. I observe these things. These form my knowledge and my works reflect the knowledge, the feelings, the dilemmas, I have absorbed.” As evident from his words, he belonged to a rare species of filmmakers for whom cinema is the art originated from and catering to the subconscious, where all interpretations make way for a meditative experience. Such filmmakers elate cinema from the ground level and place it alongside music or a silent sculpture.

Written By: Ragesh Dipu

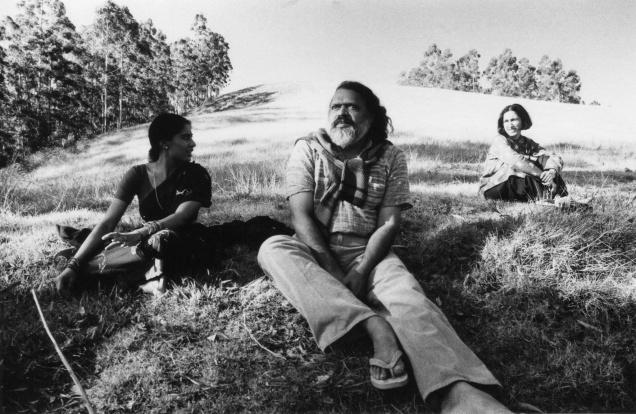

Cover Image: Smita Patil, G Aravindan and Nasreen Munni Kabir courtesy Peter Chappell