“On that side lies my home. See that houses. So near! But, I can never go in there, because that is a foreign land,” reminisced one of Ritwik Ghatak’s characters in his movie Komal Gandhar. Even though it sounds like a melancholic monolog of a  displaced and despair soul, the above reminiscence represents Ritwik Ghatak’s recurring metaphor and a haunting inspiration throughout his career, that redefined Indian Cinema. Ghatak bore the eternal wounds of the partition of Bengal in 1947 and he could never reconcile with the agony, anguish and the feeling of displacement as an aftermath. The burning experiences during the partition laid the foundation of Ghatak’s unique vision and cinematic approach.

displaced and despair soul, the above reminiscence represents Ritwik Ghatak’s recurring metaphor and a haunting inspiration throughout his career, that redefined Indian Cinema. Ghatak bore the eternal wounds of the partition of Bengal in 1947 and he could never reconcile with the agony, anguish and the feeling of displacement as an aftermath. The burning experiences during the partition laid the foundation of Ghatak’s unique vision and cinematic approach.

Born in Dhaka in an undivided India, Ghatak and his family migrated to Calcutta in his early days of his adolescence. The flood of refugees during the Bengal famine in 1943, the partition in 1947 and Bangladesh liberation war in 1971 made indelible scars on Ghatak’s sensibility. He started his journey as a theater director and tied up with the Indian People’s Theatre Association (IPTA) in the early fifties and wrote, acted and directed numerous plays. Ghatak’s ideology and socio-political outlook were in sync with IPTA in those days as many other left-wing artists and they bombarded Bengal’s cultural sphere with realistic plays depicts the lives of the working class and the common man.

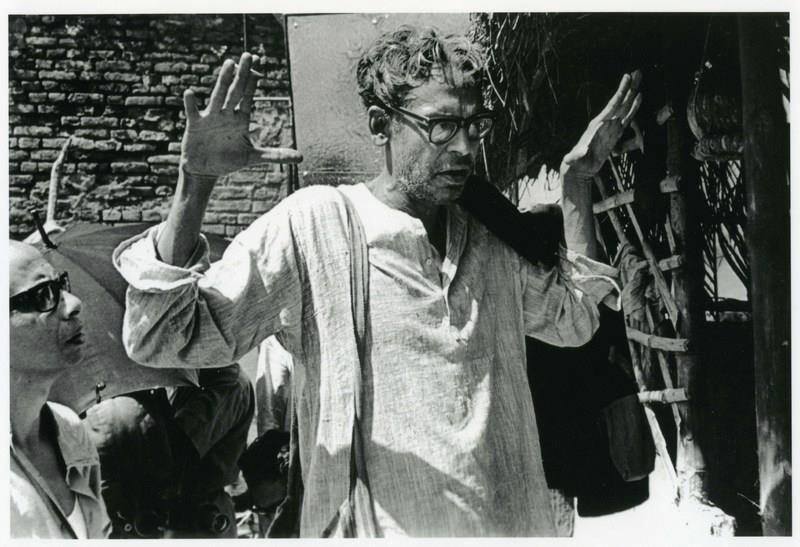

Ghatak’s major breakthrough in cinema happened when he made his debut feature Nagarik in 1952. His unique methods of mixing documentary realism with stylized performances borrowed from the theater, references to Bengali folk theater tradition and Brechtian techniques of narration announced the raising of a promising young filmmaker. Indian art house cinema movement was in its sprouting stage and Ghatak’s rebellious spirit had no limits.

He tasted his first international success when the 1958 movie Ajanthrik, the first Indian movie to depict the life of an inanimate object, a motor car, and its driver, went to Venice Film Festival. Very soon, Ghatak became a prominent force in the Indian parallel cinema movement which challenged the monopolistic, star-driven, narrative and theme conventions of Bollywood.

Ghatak stood as a lonely tower in the stream and formulated a unique aesthetic that deeply rooted in his socio-political conscience. Along with the burning political scenario of Bengal, the rivers, terrain, people, dialects, and folklore of his lost Bengal land haunted Ghatak throughout his career. Many of his works were an exorcism to take out the ghosts of the past and to heal his wounds.

Ghatak stood as a lonely tower in the stream and formulated a unique aesthetic that deeply rooted in his socio-political conscience. Along with the burning political scenario of Bengal, the rivers, terrain, people, dialects, and folklore of his lost Bengal land haunted Ghatak throughout his career. Many of his works were an exorcism to take out the ghosts of the past and to heal his wounds.

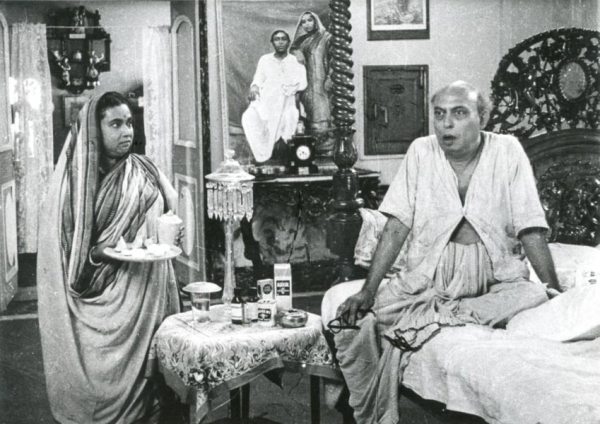

Unlike other fellow filmmakers of his generation, Ghatak trusted and depended upon intuition while making movies. He chose simple story lines to depict intense, traumatic and complex lives of middle-class families and told them in a characteristic cinematic rhythm. Despite having a bombastic commercial success as a scriptwriter in Bollywood through Bimal Roy’s Madhumati, Ghatak was never attracted the glitter of mainstream Hindi cinema.

Ghatak always chided the commercial extravaganza of emotions and sets in the mainstream cinema. The result was Ghatak had to make his movies on a shoestring budget and distributors gave those movies a lukewarm response. But, the same situation benefited Ghatak and he improvised his own methods to achieve his vision, even when the producer was incapable of providing the necessary financial support.

In the 70s, Ghatak’s cinematic language developed outward to incorporate the turbulent economic and political situation in the country. Standing in the midst of this turmoil, Ghatak explored an aesthetic “Indianness” in his movies, a quality stood him apart from his contemporaries. Ghatak took this as his mission and even fought a fierce ideological battle with his past allies, IPTA in particular and the left wing in general.

After the rift with the left wing artist brigade, Ghatak’s cinematic approach underwent a dynamic change and the director thrived for more artistic endeavors within the Marxist social realism. He either broke or bent the idioms of Marxist film critics and pulled his medium as close as possible to folklore. Ghatak found his ultimate raw materials in local and rural folk traditions in the rich Indian context and daringly applied them in his movies, which bore a universal stamp of a master filmmaker.

“Film is not a form, it has form,” stated Ghatak in one of his conversations. He also insisted that any artwork should artistically engage people and stood firm on this perspective, Ghatak continuously experimented with styles and genre. Ironically, Ghatak kept a creative distance with the cinema as a medium and opined that the key factor that holds him close to the cinema is that it can reach out millions of people at one go, and if he came across a medium better than cinema in that, he would embrace that.

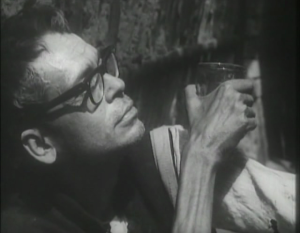

Ustad Allauddin Khan – A Documentary by Ritwik Ghatak

But, Ghatak never held this detached approach in his cinematic language, which lavishly used intense and highly emotive close-ups, exemplifying his humanistic approach. Ghatak was rather whimsical in his editing methods and often, he searched the same haunting question, “what is cinema”, on the editing table. The film theoretician and teacher in Ghatak came into full blossom during his short stint as a teacher at the Film and Television Institute of India, Pune in the 60s and he wrote voraciously about cinema with a philosopher’s eye.

Ghatak’s turbulent and eventful career spanning around 50 years left 8 feature length films and numerous documentaries, plays, essays, and books. His major movies are Nagarik (1952), Ajantrik (1958), Bari Theke Paliye (1958), Meghe Dhaka Tara (1950), Komal Gandhar (1961), Subarnarekha (1962), Titash Ekti Nadir Naam(1973), and Jukti Takko Aar Gappo (1974). Unlike other Indian masters, Ghatak always posed a question of placement on the face of film students, that perplexed them by offering a wide range of artistic explorations, rich with visual motifs and innovative approaches. Perhaps, the film historians may find him in that gray area where, socio-political-economical credentials of a filmmaker overlaps with his aesthetic parameters, a place where Ghatak always fought his battles.

Written By Ragesh Dipu