Most beloved actors/actresses have a cringe-inducing film (or four dozen) waiting to ensnare you if you’re not careful. The call of undiscovered delights pull you deeper into filmography frontiers, but the further you dig into undocumented catalogs, the more you put yourself at risk. Things are seen that can never be unseen, and we can all agree to forgive and forget and definitely never speak of them again. But there’s no excuse for watching a film you KNEW was not representative of an actor’s strengths, and then b*tching about it, anyway.

Thus, I have no one but myself to blame for Amanush (1975), however much I’d like to. ‘Cause I knew darn well what I was getting into. In case you are out of the fandom loop, there are three [painfully obvious] reasons why it should be avoided:

- Uttam at any age is at a disadvantage when forced to communicate in English or Hindi.

- In Beth of BLB’s words, “Color Uttam is not good Uttam.”

- Even in black and white Bengali films, in the mid-1970s, his hero energy is rapidly deflating … though he retains his good-natured humor and continues to flash his boyish grin when given the opportunity.

But despite all these indisputable strikes against it, Amanush was a hit, and it’s still spoken of in almost sacred terms in many quarters.* My Hindi-Urdu prof this semester told me the only thing of Uttam’s he had ever seen was Amanush … and this was said in such reverence that I had to take an interest. I mean, curiouser and curiouser. [You can see how the cat got killed … ]

As I was watching Amanush piece by painful piece, I was also working my way through Kalankito Nayak (1970), an Uttam/Sabitri/Aparna film that bears a lot of thematic similarities to Amanush and almost follows the plot of a typical Shakti Samanta “man-against-the-world” melodrama [Amar Prem, Khwab, Ajnabee]. Thus, it was impossible not to compare the two … their differing emotional impact (on me) and how/why they chose to go in very different (probably industry-specific) directions. Note: There’s nothing substantial to be found about KN online, so I can’t say if it wielded any influence on Amanush. I doubt that it would have unless it was a hit, but then, who can predict that sort of thing?

A quick breakdown of the similarities and differences:

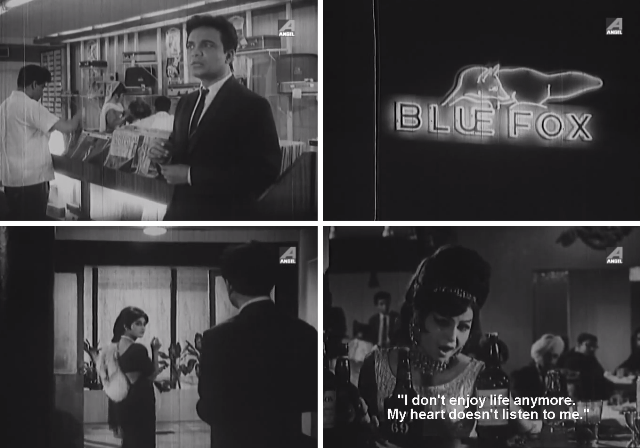

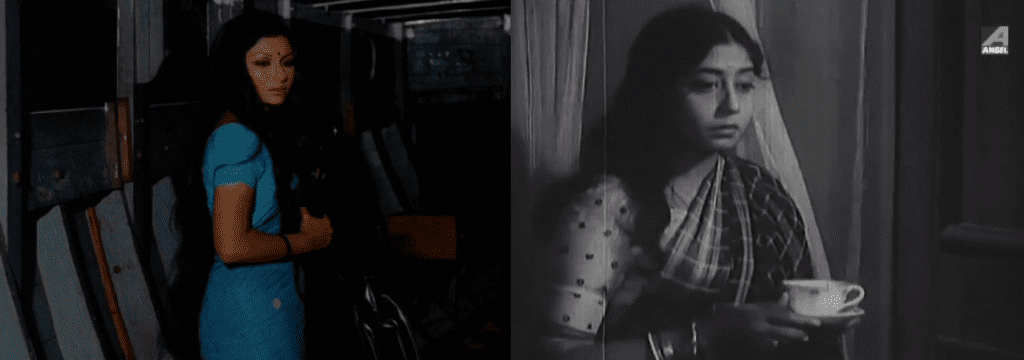

*Amanush tells of a rural landlord’s son Madhu (Uttam Kumar) who is betrayed by his family’s employee and set up as a thief and father of village girl’s illegitimate son. As a result, Madhu is rejected by his fiancee (Sharmila Tagore) and after serving jail time, loses his family land and becomes the town drunk. Because of the efforts of first-hostile, then sympathetic lawman (Anil Chatterjee), Mr. Amanush (half-human, half-beast) starts to climb up out of the muck. [Literally. He works in a mud pit.] Kalankito Nayak is the tale of a simple, recently married businessman Indrajit (Uttam Kumar), caught between helping a cast-off wife/prostitute (Aparna Sen) and the increasing suspicion and judgment of his family … stoked by the manipulation of his crooked accountant/cackling brother in law.

*One is a Bengali film clearly using Hindi film tropes, the other is a Hindi film (primarily) using Bengali film actors.

*Both heroes have hostile, distrusting, but brainwashed ex-wives/lovers.

*Both feature Utpal Dutt as a scheming character working the system.

*Amanush is told partially in flashback, but other than a brief courtroom story hook at the beginning, Kalankito Nayak is a linear, chronological affair.

*The family is the enemy in KN (starting from the first horrible acts by the hero’s mother, down to the hero’s own family bringing him to court in the climax), and is easily comparable to the community’s role in much of Amanush. Both heroes are essentially misunderstood creatures, cheated by their employees, unfairly ostracized by their social groups, and unjustly accused/punished by the law. Ultimately, KN’s hero must do the right thing when everyone believes that his actions are wrong, and Amanush’s hero must do the right thing when he no longer believes in himself.

A longer breakdown of the similarities and differences:

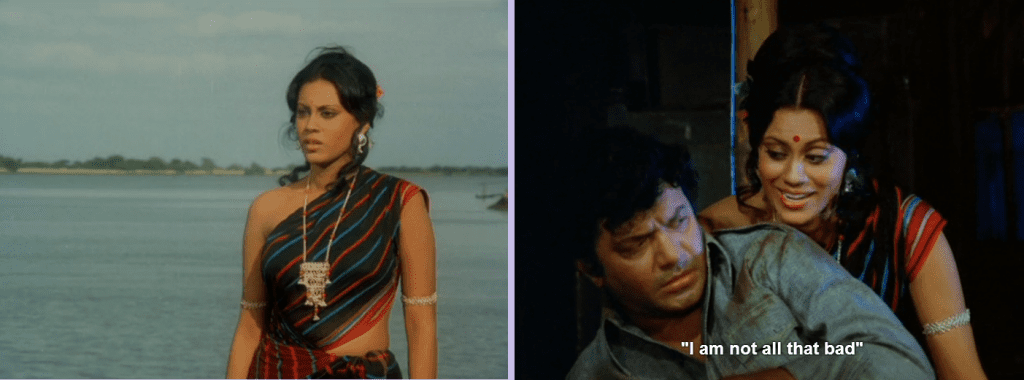

You can’t talk about Amanush or even Kalankito Nayak without comparing them to the most inescapable of Bengali story arcs, that of the Devdas-ian hero. In fact, in both stories, the only empathetic figure for a time is the golden-hearted prostitute.

As tends to be true of Bengali classic films, KN’s characters act in less extreme ways than a comparable filmi hero (one night of drinking instead of a hundred) but will still undergo extreme consequences. When first ostracized by his family in KN, Indrajit begins to drink but gives it up fairly quickly. Yet, the mere appearance of an alcoholism is enough to cause his reputation to plummet. The character’s real struggle isn’t alcohol, but society’s quickness to judge.

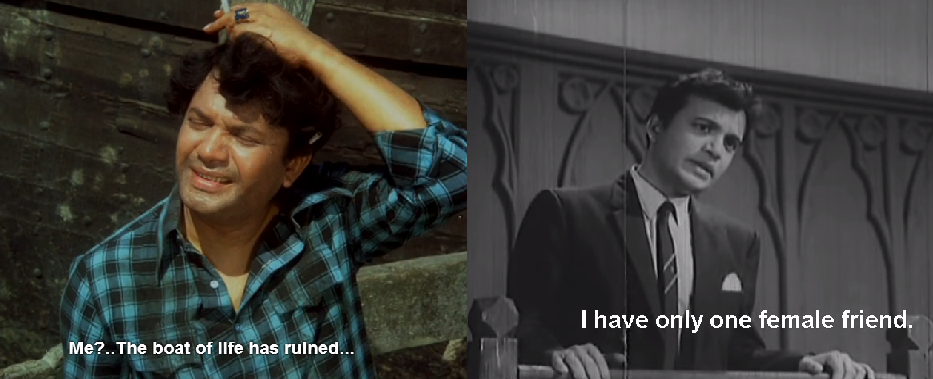

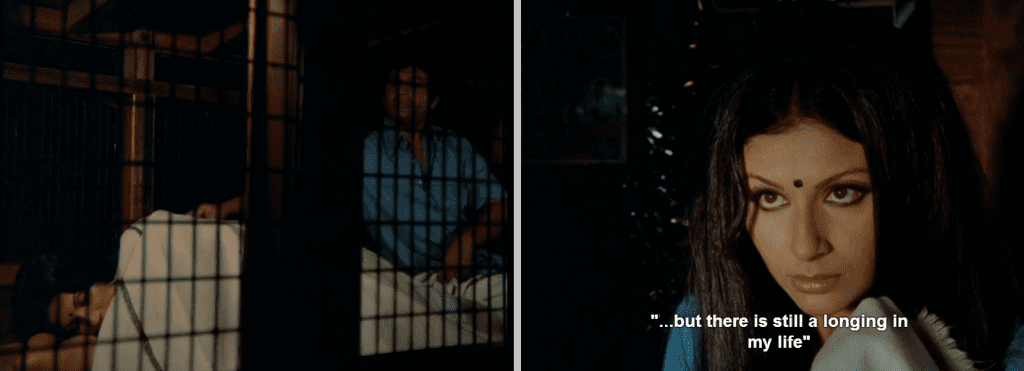

In contrast, Amanush’s protagonist is certainly an alcoholic, and must fight his own addiction as much as the ostracism of his community. I suppose this is a much bigger task, and yet I struggle to like Madhu. Much of the Amanush is one painful drunk scene after another, but by the end (if you’re still watching), the alcoholism is conquered along with the accompanying hopelessness. Perhaps, for people at the time, this was an encouraging twist on the usual tale. “Hey, you guys! Devdas goes to rehab and actually gets the girl!” And on paper, I would guess that this is a commendable plot idea, to reject fatalism and embrace self-change. However, this idea is unraveled by the implementation. Most interactions between characters are overwrought (even by the standards of melodramas), probably because their motivations and complexities are crippled by the wooden dialogue.

Note: I’d be interested to hear opinions from anyone who speaks Bengali about the Bengali version of the film. I’d like to think I’m far enough along in Hindi to know a well-written conversation when I hear it, and Hindi-Amanush doesn’t deliver on that front … no matter what all the nostalgic reviewers claim. But scripting processes are complicated, and I’m willing to entertain the idea that in moving between English, Bengali, and Hindi scripts … or in accommodating non-native speakers, good concepts were watered down for easy translation.

As far as I can tell by subtitles (and by listening for repetitive phrases in the Bengali dialogue), Kalankito Nayak is minimalistic rather than simplistic in its ideas. This distinction doesn’t necessarily make a film good, but I will say that I was far more engaged in the motivations of its characters than Amanush’s … as I could see a believable build up to a point of view, good reasons behind misunderstandings, and the slow burn shaping the character from a weak man into a strong one. Both films attempt to do the latter and I do appreciate a REAL arc (who needs a character that is perfect from point A to point B?) but Uttam’s characterization is as bloated as his character in Amanush. In Kalankito Nayak, he pulls a bit of a Mem Saheb, his archetypal weak to strong hero (in my mind at least), and shows us a compassionate man who has weathered trials and come out the better for them in the end. I really believe that this is what Amanush attempted, and I must give it points for the effort. Perhaps if Amanush had been made even five years earlier, Uttam would have been able to overcome the bad scripting and still achieve that larger goal through force of personality alone.

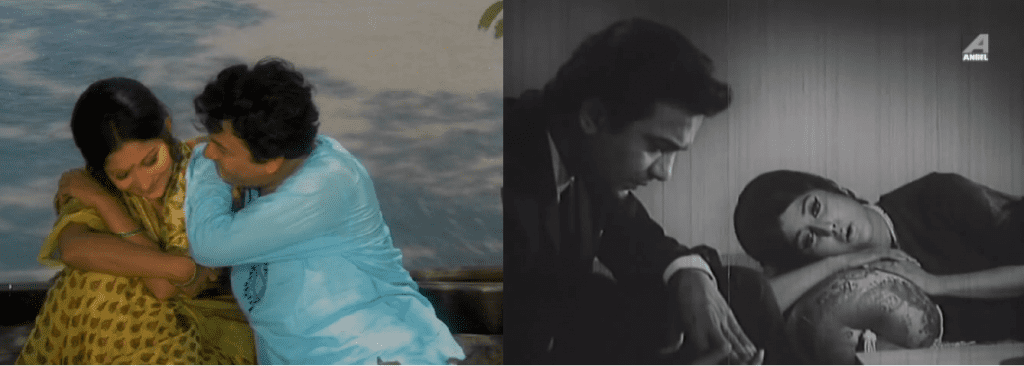

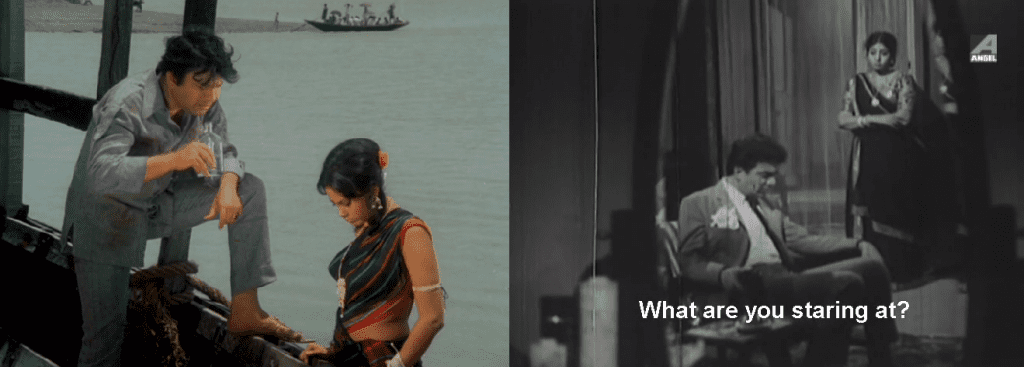

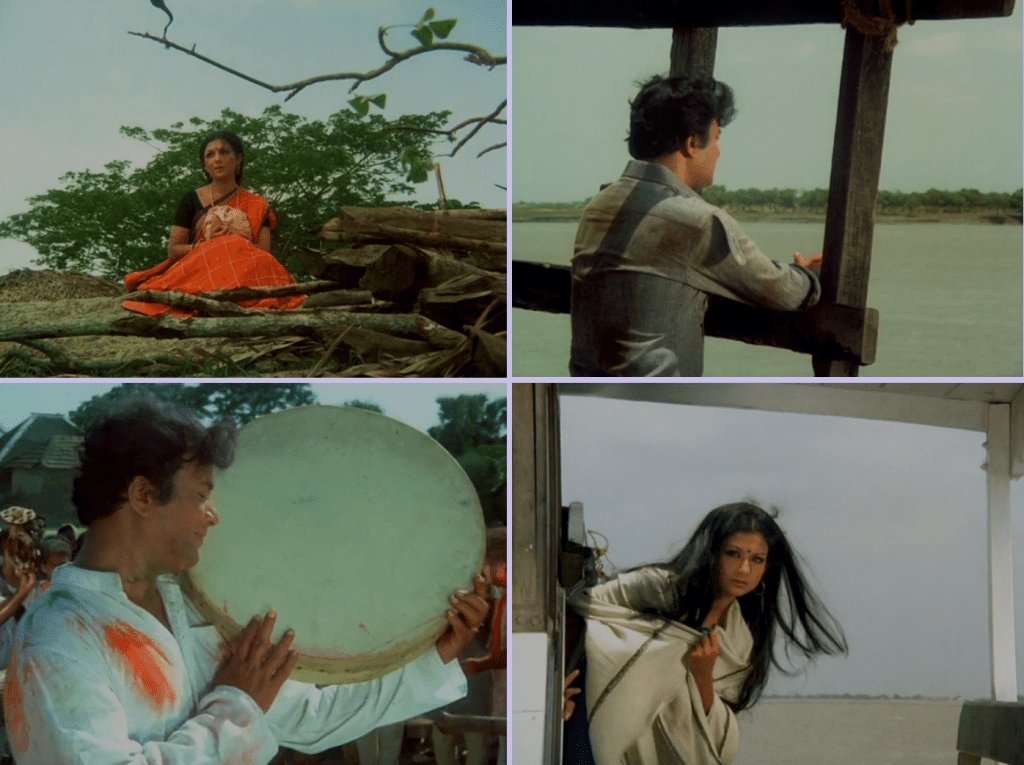

The strongest bit of Amanush, in my opinion, is also the sequence truest to Uttam’s Bengali persona and is, I suspect, a large part of why the film is often called “sensitive.” I’m speaking of the progression of scenes on the riverboat in the second half.

The hero and heroine are thrown together long enough to show the heroine that her reject still cares for her (and is pretty much the only worthwhile dude around, even if that doesn’t say much). It all culminates in a bittersweet song of lament, the hero’s face toward the wind, finally freed from the censoring expectations of city and community, and virtually unaware that his beloved is listening. [Actually, now that I think of it, KN’s only stand out song is a beautiful lament as well.] The piece works well in both Bengali and Hindi versions and is also a sequence that would have fit just as comfortably in any commercial film from 60’s Calcutta. I for one find it hard to swallow Bengali songs in pastoral settings, or those free of performance-logic, as I instinctively feel the actors straining to legitimize something so unleashed from reality. But, for whatever reason, on a boat or on the water’s edge, suddenly, everything seems possible. My favorite Bengali songs (especially into the late 60s and 70s) are often on harbors, rivers, and beaches.

Perhaps it works because the crew and actors felt comfortable, or maybe because Shakti Samanta has a natural directorial eye for scenes on the water or near the water … in fact, as I mentioned in my last post, he tends to work water-recreation, boats, and bathing suits into scenes in his films that would usually be shot in a forest or a garden. They’re often standout sequences, too. Just think of the water-skiing song with Shammi hanging from a helicopter in An Evening in Paris, or the rowboat song on the lake in Kati Patang.

This is one of the only things Amanush does have over Kalankito Nayak … an attention to beauty. Sharmila is somehow even more luminous than usual. Perhaps because she is without her bouffant, and because Samanta always frames her with adoration, as one does their chosen goddess. Her character has little to do except be a thorn in the hero’s side, but she’s still a presence. I couldn’t help but shiver at one point when she emerged above deck, hair blowing around her in a whirlwind.

Related to this, Samanta gives Prema Narayan far more screentime than usual. She even gets a song all to herself for once! She’s really the only person who is consistently likable in the film, acting as the audience’s umbrella for the buckets of tears from the main character. Perhaps this nonconformity is why the retrospective in The Hindu [asterisked above] found her un-affecting and wooden. Her Dhanno might have been the faithful Chandramukhi to Madhu’s Devdas, except for the part where she pushes Devdas to change and actually gets to dishoom–dishoom the group of hooligans abducting his beloved. [I can’t remember the last time I saw a woman come to the aid of another woman this way in a Hindi film. It was probably something with Aruna Irani and probably ended in her death.] This is another cross-point between the two films, the relationship between the two major female characters–the wife and prostitute–is not a hostile one. The Kalankito Nayak wife/call girl relationship is the more filmi (i.e. hopeless) of the two, while Amanush pleasantly allows Dhanno to be free of the usual pine, sacrifice and die arc.

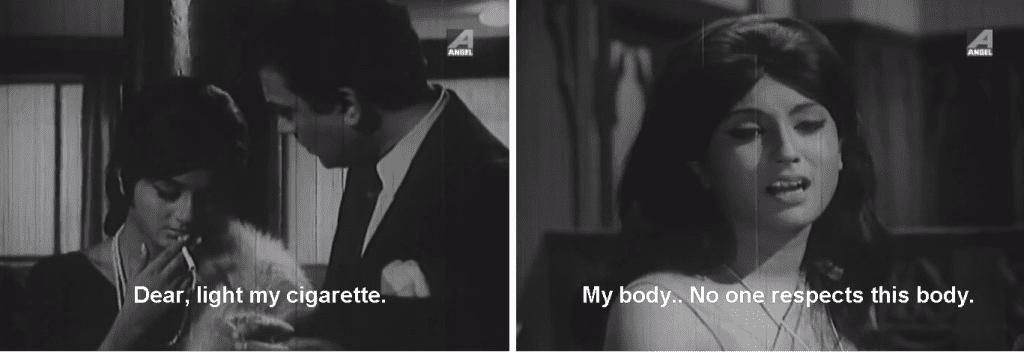

However hopeless her story, I must admit that Aparna Sen as “the loose woman who asks you to light her cigarette at a party, then languidly drapes herself across a couch as if she is in the last stages of consumption,” is my favorite Aparna Sen.

The more I see of Shakti Samanta, the more I want to examine his films for his own personal motivations. Not because I idolize his work, but because I wonder why I am consistently drawn to his particular flaws in spite of myself. For example, when watching Shakti Samanta melodramas post-Rajesh craze, I still feel as if the stories are written for a Rajesh-like star. I’ve seen a few with Mithun that are basically just re-workings of different elements from Rajesh films (i.e. Khwab, Aar Paar). Watching Amanush, I felt the same … as if Amar Prem’s Anand Babu had just been given a more masala-appropriate backstory. Of course, Amar Prem was based on a Bengali story and a Bengali film, and Uttam played the Bengali film role of Anand Babu, so now my brain is officially exploding.

Also, whether it’s 1975 or 1985, Shakti HAS to put his heroes in plaid shirts whenever the chance arises–and it seems to me that this is a small symptom of the interchangeability of his melodrama’s male leads. It’s not that Shakti is the only one to do this–most masala films feature a familiar hero–but after watching a few Samanta films in quick succession, one is tempted to ask, “Would this role have fit better on Rajesh, Mithun, etc.?” The bits of masala, such as the constant mud-fights with Uttam struggling to lift the goonda up even as he yells “Ut, ut, ut!” certainly gave the mid-70s audience the action they were looking for, but unfortunately, cast a non-action hero (like Uttam or Rajesh) in an unappealing light. I’m just saying: casting, casting, casting is as important as location, location, location. Obviously Shakti Samanta knows the latter, but when his films fail, I think it’s because he disregards the first. Surely some of Uttam’s star power shines through in Amanush and led to its success, but it is so much the less when you know what he is capable of with homefront advantage.

When Kalankito Nayak fails, it is because it runs the risk of moralizing instead of entertaining. It doesn’t completely succeed in winning your heart. It does ask important questions and gives a prescription for action … a prescription I mostly agree with. I like that usual ideals–self-sacrificial wife and long-suffering prostitute–are given a semi-critical treatment. The film appears to say that the instinct to suffer instead of communicating one’s needs is a dangerous and needless one. Like, “Ladies, if a progressive man (embodied by Indrajit) doesn’t require this of you, then nor should society, and especially not you.”

Both films emphasize the need for the law (the courts in KN, the local police in Amanush) to look beyond reputation or the appearance of evil. As in many masala films, we see that when the law listens to rumor and generally held “truths”, it runs the risk of condemning innocents. But here, the community is as much at fault as the law. Neither the informal social control wielded by the family in KN nor the condemnation of the village in Amanush escape criticism. In Amanush, the lovers *spoiler* resolve their differences not when the estranged fiancee knows the truth, but when she is willing to stop caring about what the rest of the village will think of her. Via more or less painful paths, both films stress the importance of trusting the people you love, and not giving a damn about what society thinks … ’cause, hey, society is wrong, more often than not.

In Kalankito Nayak, the newlyweds make a promise to one another to always talk through misunderstandings. Eventually, it is this promise that the wife returns to, realizing that sacrifice is not a good substitute for honest conversation. This summarizes (for me) the deeper impression that both stories leave: Listen before you judge … you probably don’t know what the heck you are talking about.

Somebody write in quick and tell me to apply the same logic to Amanush, I’m a judgy mess.

Written By: Miranda Brist

Caution: The opinion expressed in this article are the personal opinion of the author. Bollywoodirect is not responsible for accuracy, completeness, suitability or validity of any information in this article. The information/Opinion, facts appearing in it do not reflect the views of Bollywoodirect & Bollywoodirect doesn’t assume any responsibility or liability of the same.