In the interview for membership of ASC, the American Society of Cinematographers, he was asked how many feature length film he had shot and he casually replied Seventy. The board took that for seventeen and he had to correct them. The next question was how many movies he made with Ingmar Bergman. “Ah, that’s seventeen,” replied Sven Nykvist, the colossus among cinematographers. The Swedish-born Sven Nykvist, the first European cinematographer to join ASC, had around 120 movies in his kitty, many of them are real gems of world cinema. The Academy honored him twice with the Best Cinematographer prize for Cries and Whispers in 1973 and Fanny and Alexander in 1983, both directed by Ingmar Bergman.

Editing, The Neurotic Fine Tuning of Visuals, An Ingmar Bergman Approach

This interesting video is a stepping stone to the life and work of Nykvist and concisely describes his journey in four eras, formative, Bergman, simplicity, and Hollywood. Born to Lutheran missionary parents, who had a religious dislike for cinema, Nykvist was brought up by his Swedish aunt. Ironically, his father was an amateur wildlife photographer. When Nykvist was 16, he worked for a local newspaper and managed to get an 8 mm Keystone camera, which kick-started his journey with visuals. At the age of 19, he became an assistant cameraman and in 1923, turned an independent cinematographer, working with small productions in Sweden and Italy.

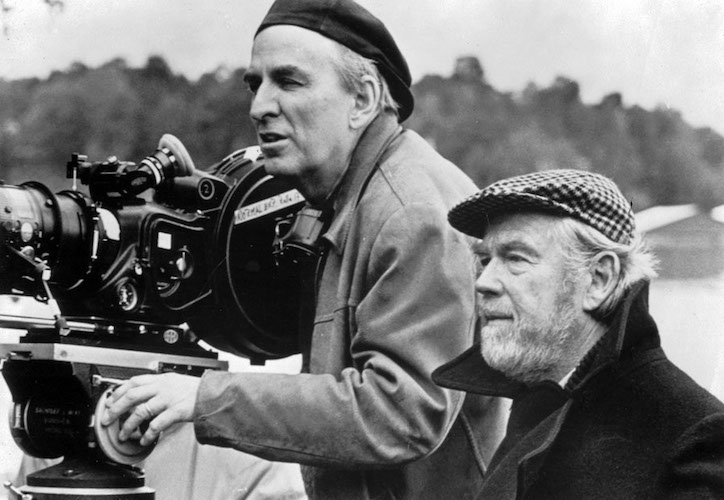

Bergman roped him for the first time in his 1953 movie, Sawdust, and Tinsel, and Nykvist eventually became Bergman’s third eye behind the camera. Nykvist’s creative influence on Bergman was so intense that, the filmmaker invented an ingenious cinematic approach. On the other hand, Nykvist’s style was also influenced to a great deal by Bergman and together they formulated a new aesthetics in world cinema. It was an explosive union of a hard to please, short tempered, genius filmmaker and a patient, ready to experiment and daring cinematographer.

“Had I not met him,” says Nykvist, “in all probability I would have remained just another technician with no great awareness of the infinite possibilities of light.” A great deal of Nykvist’s inspiration came from paintings and still photography and like Bergman, he was an ardent lover of light and its shadow games. Born in Sweden, Swedish, a place which has summer days in which the sun never sets and winter nights in which the sun never rises because of the country’s geographical position, Nykvist was well aware of the importance of light and its ability to create particular moods for the movie.

The Image That Comes Out of A Cinematographer’s Head, It’s Roger Deakins Speaking

Nykvist was often emotionally connected with the characters and so immersed in the performance so that he forgets to check the viewfinder. With Bergman, Nykvist devised a unique style of logical realism in cinematography that utilizing natural light to the maximum and ingeniously using the patterns and tonal shifts of the natural light to create various moods in the movie. “Naturalistic light can be created with fewer lights,” says Nykvist, “sometimes none at all. At times I have used only kerosene lamps or candles.”

He was a darling among the actors because he never irritated or disturbed them with harsh light or light meters and always briefed the actors how he had been going to light up them. Nykvist’s soft lighting, naturalistic style went to places and his expertise to light up faces gained a lot of admirers from the international filmmaking community. And very soon, he got a call from the legendary Russian auteur, Andrei Tarkovsky to make Sacrifice, which is considered as one of the greatest movies ever made in the history of world cinema.

Nykvist lists four points inevitable to become a director’s cinematographer. 1. Be true to the script. 2. Be loyal to the director. 3. Be able to adapt and change one’s style. 4. Learn simplicity. The legend says Nykvist never stopped thinking about light, even at home, and his living images are testimonies.

Written By: Ragesh Dipu

Image Courtesy- alchetron.com