P. K. Nair’s Internationalism

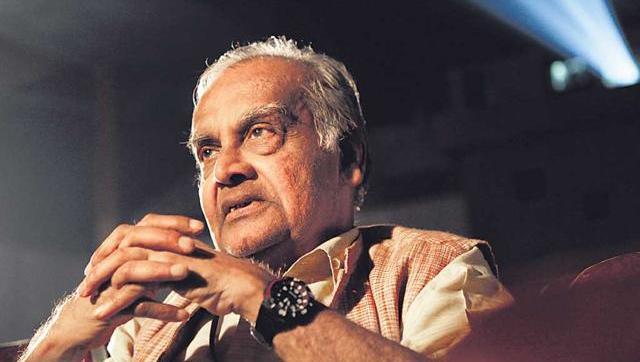

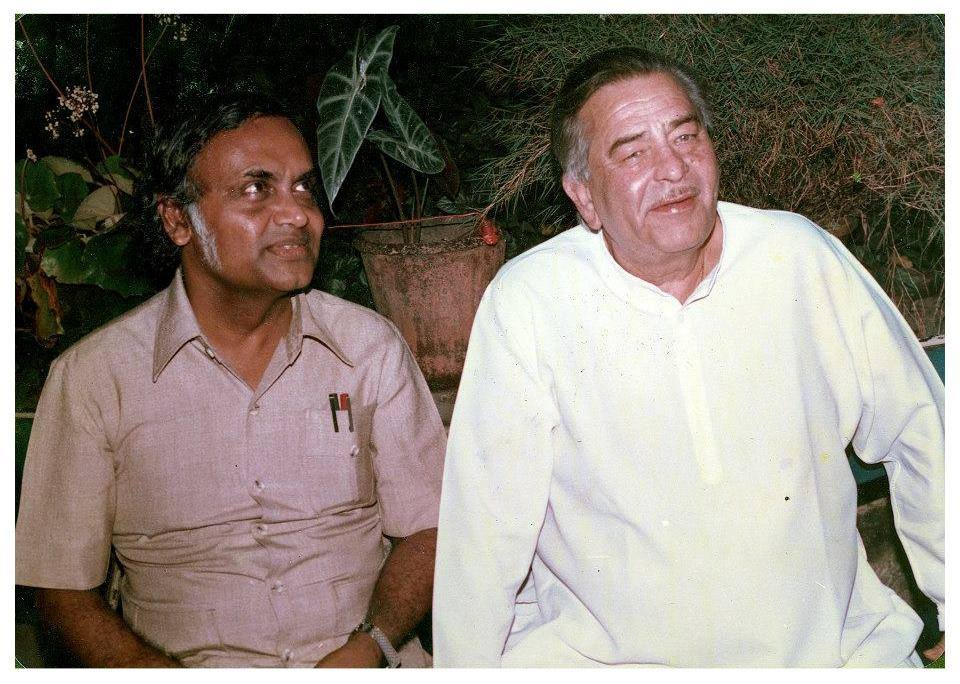

The death in March 2016 of Paramesh Krishnan Nair (better known as P. K. Nair or Nair Saab ), the former Director of the National Film Archive of India (NFAI), and subject of Shivendra Singh Dungarpur’s award-winning 2012

documentary ‘Celluloid Man’, was followed by an outpouring of emotion from friends and colleagues in the world of filmmaking and cinema preservation.

Two years ago, Nair discussed his thoughts about cinema with us in person, which we also recorded and broadcast with his permission. We find now that we’re in the unexpected and in some ways unwelcome, situation of having recorded the last long interview with P K Nair, on films and on his legacy. We edited over five hours of conversation over several days down to a 25-minute sequence, aired earlier this year on London’s arts radio station Resonance FM.

The P K Nair whom we met in his final years was often wickedly funny in his devastating put-downs (describing one Bollywood megastar for posterity as a ‘nonentity’, for example we’re sure she’ll be ecstatic when we air that sound-byte, eventually). While an 80 year old Nair was sometimes slow in gathering his thoughts and in replying, what he had to say came forth in the dignified, precise, highly detailed paragraphs of intense and deeply humane insight – not only observations about cinema but about Indian history, culture, and about the human condition generally – for which the people close to him both respected and loved him. He was generous in sharing his knowledge with students and visitors.

In Shivendra Singh Dungarpur’s documentary on Mr. Nair, ‘Celluloid Man’, film director Vidhu Vinod Chopra who was an FTII student in the mid-1970s recalls Nair loaning him the precious NFAI print of Godard’s ‘À bout de souffle’ (‘Breathless’, 1960). “He said, ‘take the print and study.’” According to author and film scholar Suresh Chabria, NFAI director from 1992 to 1998, “for students of the film institute in the 1970s and ’80s, he was a cult figure because he freely showed them films from the archive.”

P K Nair’s astonishing achievement was to physically locate and preserve as much of India’s film heritage as could be managed from 1965 until his retirement as NFAI Director in 1991. Starting as an Assistant Curator with the censor’s small collection of films which had won the Indian National Award, Nair went onto to become NFAI’s Director in 1982, preserving around 12 000 complete prints before his retirement. These included films by legendary directors Satyajit Ray, John Abraham, Raj Kapoor, Guru Dutt, Ritwik Ghatak, Mrinal Sen and V Shantaram.

Around 8000 of the films in the collection which Nair secured are Indian but, significantly, another 4000 – one-third – are international films. These include work by Bergman, Kurosawa, Fellini, Andrzej Wajda, Miklos Jancso, Krzysztof Zanussi and Vittorio De Sica.

The collection now stands at around 15 000 films. Under Nair’s direction, NFAI acquired about 460 films a year. It has continued to take on 120 films per year on average since then, in a country where there’s no legal requirement for movie producers to deposit copies of their work in the national archive.

Nair was closest in his philosophy of preservation and curation to Flipside, Langlois’s Cinématheque in Paris, and to Britain’s Channel 4 television which screened world cinema and film classics in the ’80s and ’90s. Nair saved Ray and Abraham for future generations. He did this because he was trying to save everything. We asked him what films, in particular, he wished he’d saved for posterity. His initial answer was simple: “everything.” Nair had the same zeal for saving a Ramsay Brothers horror film that he did for saving a classic. He knew that it was impossible to know from a present vantage point what future generations would consider as having relevance or significance. Therefore it was imperative for national film archives to keep everything. He imbued in all of his colleagues and students this militant eclecticism as a fundamental principle.

As NFAI Director, P K Nair also screened everything. At his wake, friends and colleagues vividly recalled Nair screening counter-culture films such as Emile de Antonio’s searing analysis of the road to the Vietnam War ‘The Year of the Pig’ (1969), another anti-war Vietnam film ‘Hearts and Minds’ (1974) directed by Peter Davis, and Mike Nichols’ ‘Carnal Knowledge’ (1971). He was able to do this because – despite having a government job – he had the only one he would ever want. Nair was uninterested in promotion through India’s civil service or in politics in the sense of gaining office or status, although he was an astute political observer. “Nair’s only destination was NFAI,” a former colleague told us.

Keeping more than 15 000 prints safe for future audiences and scholars is an incredible feat but it’s far from being the extent of P K Nair’s legacy to world culture. His vision for the Mission of NFAI was broader, more ambitious than that of, say, BFI which is to preserve British films. The death of NFAI’s formative Director has prompted a renewed effort by the present leadership to re-evaluate the archive’s holdings and the overall history of its intake. An interesting question for scholars to consider in the future is the proportion of foreign prints permanently preserved in India’s national archive since 1991, and how the curation and exhibition of NFAI’s collection of world cinema has influenced filmmakers and film appreciation in India since the ’60s.

Nair’s life’s work was the study and preservation of world cinema, and to form an internationally relevant and contemporary collection which placed Indian films in their rightful place in that broad, global and constantly evolving context. In this sense, Nair had a lot in common with video CD pirates on market stalls the world over, and with the file-sharing community on BitTorrent and specialist sites like Karagarga – stripping cinema of its inherent value as a commercial product and liberating it for its greater artistic, historical, political and social relevancies.

From many hours of conversation, we were left with a clear sense that Nair’s intention in running NFAI from 1965 wasn’t simply to create a reliquary for the sacred objects of Indian cinema, for future study and veneration of a world class “brand”. Retaining and restoring the film heritage of one billion and counting people was part of his Mission, but Nair was focused on looking at all cinema – made everywhere in the world – in terms of the development of a new kind of human expression and Art. Saving India’s films were axiomatic due to the sheer volume and range of movies produced in over a century. NFAI’s collection also includes films from France, Italy, Central and South America, and countries of the former Soviet Union.

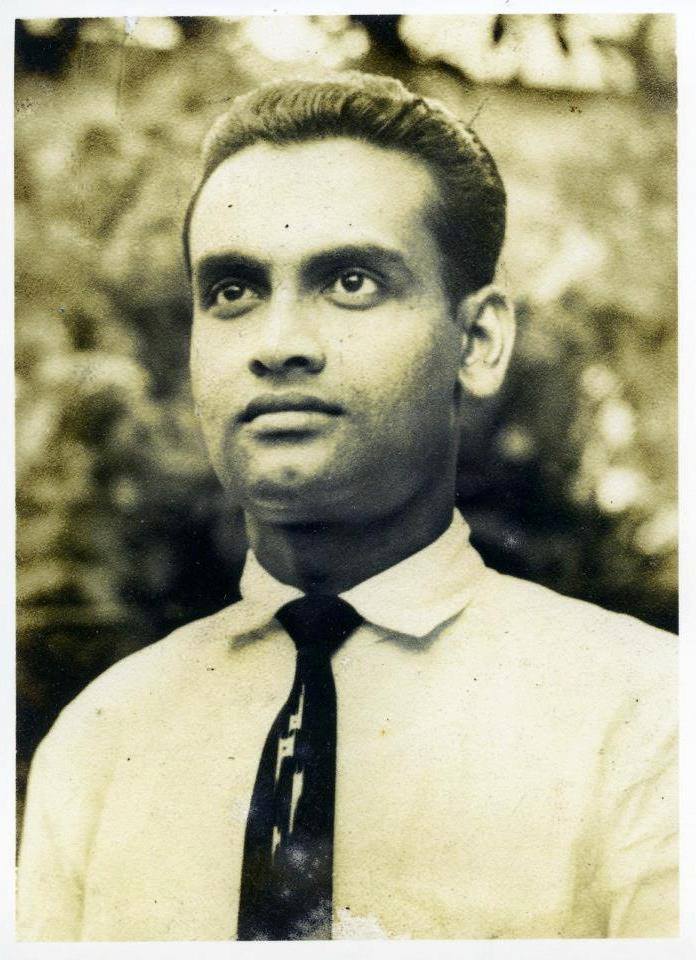

A remarkable 1974 FTII student film shot on 16mm was screened on the spur of the moment at NFAI as part of its restoration course, to honour Nair on the day he died. ‘The Archive’, directed by Uday Shankar Pani, is a ten minute black and white guide to the institution, as Nair was embarking on the main part of his life’s work. Sitting at his desk, a dark haired Nair with a commanding gaze but relaxed manner (he was, as it happens, a very handsome fellow) explains the role of the NFAI in preserving world film heritage. This point is emphasised soon after by a handheld sequence which moves through NFAI’s documents library. A huge still of Greta Garbo looms into view. Then, a moment later, the shot is of a poster: an African American face looks out at us from a wall, above it the words ‘No Vietnamese Ever Called Me Nigger.’ (A famous quote often misattributed to Muhammad Ali).

‘The Archive’ is an important document in understanding Nair’s legacy and place in international film history, and is in this respect a companion to ‘Celluloid Man’. It deserves a wider audience, and for FTII and NFAI to digitise and exhibit it, either online or as an extra on a future DVD issue of Dungarpur’s documentary.

According to his former NFAI colleague and now respected academic Gayatri Chaterjee, in the early ’60s Nair acquired most of his appreciation of film criticism and its Left-wing political milieu from reading international film magazines while hanging out at FTII in Pune. “When I arrived, quite late, by 1980 we were getting Cahiers du Cinéma, Positive, along with Film and Filming, Sight and Sound, Jump Cut, the trades. He knew of the Cannes film festival, Langlois, Cocteau, all those people”.

“People say he wanted to be a Langlois. He fashioned himself exactly as he wanted to be. For example, did the Ministry [of Broadcasting and Information] know Nair was showing the students ‘Hearts and Minds’, ‘The Year of the Pig’, all the South American films meticulously being shown?”

It’s striking how in the ’80s Nair was embracing the political and international contexts of film conservation and exhibition. His attitude to what was preserved and what was shown is startlingly contemporary, more like reality as presented on YouTube: a flat, nonlinear yet plastic version of history where all points on the map are of interest and are equally worthy of contemplation and discussion.

His sense of the complexity of India’s film heritage was not only looking outward but also inward. One regret he expressed to us on the record was that, despite – or perhaps because of – his government position, he was unable to visit Pakistan or have any bilateral relationship with India’s neighbour.

Nair’s appreciation of the internal complexity of Indian cinema in its origins is reflected in his list of 21 missing film treasures he was unable to locate, which he collated originally for UNESCO in the ’80s. The list is comparable to the BFI’s Most Wanted list. A fitting tribute to P K Nair would be for Indian film historians and their colleagues around the world to continue his work by adopting the list of 21 films as a call to action.

Nair told us at the end of our interview: “Even if one or two reels turn up, it would be a great thing. I would put it as a revelation.”

Last month, the NFAI acquired rare footage (approximately 28 minutes) of ‘Bilwamangal’ aka ‘Bhakta Soordas’, a 1919 production of the Elphinstone Bioscope studio which would later evolve into Madan Theatres, one of the most prolific Indian studios of the silent era. Thus far, ‘Bilwamangal’ remains the only surviving film of Madan Theatres and J.F. Madan, one of the most important silent-era filmmakers of India.

This acquisition was made possible under the FIAF framework of mutual exchange, with the NFAI receiving the footage of ‘Bilwamangal’ from the Cinémathèque Française in exchange for a digital copy of the 1931 Indian production ‘Jamai Babu’.

This momentous find for the NFAI underscores the collegiate, collaborative and international spirit which is at the heart of the film preservation and archiving community, and which thrives by treating cinema heritage as ‘world heritage’ rather than cultural artefacts of individual nations. It is this spirit which Mr. Nair and his international archive embodied. It is this spirit that will keep his legacy alive.

Written By- Shruti Narayanswamy and Tim Concannon

Image Courtesy: Hindustantimes.com

Also Read: Cinema – The Heritage in Danger?

Caution: The opinion expressed in this article are the personal opinion of the author. Bollywoodirect is not responsible for accuracy, completeness, suitability or validity of any information in this article. The information/Opinion, facts appearing in it do not reflect the views of Bollywoodirect & Bollywoodirect doesn’t assume any responsibility or liability of the same.