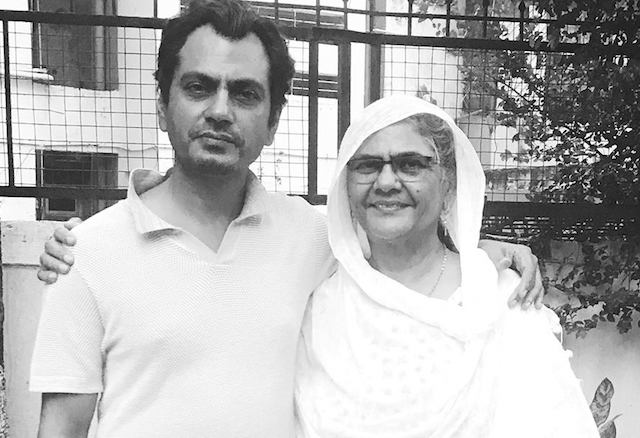

“Ammi” Excerpt From An Ordinary Life: A Memoir By Nawazuddin Siddiqui

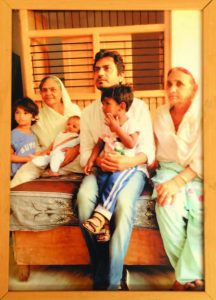

My Ammi’s parents named her Mehrunnisa. They must have been psychic because the name’s meaning—a lady who showers love—is exactly what Ammi is. Everyone called her Mehrun for short. She came from a village called Gairana, which was even smaller than ours. So her dream of me becoming something in life was even bigger. But she was well educated for those circumstances, for those times.

There was a tradition of education in her family. Aur yahan awaragardi ka mahaul tha—children in our village often did not bother to complete their studies and went straight to work. Ever since I can remember, she kept pushing me to study, wanting me to become something and get out of Budhana. During Eid and other festivals, like most women, Ammi too wanted to wear bangles. Those were days of brisk business for Dadi’s brother and he would also bring Ammi bangles. But we would not even let him enter our house. Ammi would simply let her hand out of a window or the front door, leaving the rest of her unseen, and he would make her wear bright glass bangles, first in one hand, then in the other.

He seemed like a simple, loving man, and even as a child I knew that he loved me a lot. However, I never went to his house. Nor did we ever let him enter our house, all because he was a Manihaar. In fact, everybody would tease me about my dadi’s background. It was a joke to them, but gosh, did it sting! I’d put up a brave front as if unaffected by their harsh words and ask these bullies to fuck off.

But later at home, I’d run and hug Ammi, wailing and complaining about how hurtful it was. I’d keep telling her, let’s all move out of this shitty place. What was here anyway! So you see, Ammi and I both wanted me to leave my hometown for all sorts of reasons. Ammi must have educated close to 150 girls in total. In fact even today, Ammi can be found teaching four or five girls. Her voice can be heard across the corridors correcting the pronunciation of simple words like Raheem and stressing over the phonetic perfection of the ‘r’ and the ‘z’ sounds. Naturally, she taught me Arabic as well. I am so fluent that I understand Middle Eastern films perfectly, I don’t need subtitles.

Ammi used to beat me a lot. I would stay out all day, playing all kinds of games—kanche (marbles), gilli danda and my favourite, flying kites. Ammi wanted me to study while I just wanted to play.

I remain very close to Ammi till this day. In our area, at that time sixth grade was considered college. So when I was in the fifth grade, a deposit had to be paid to secure that spot well in advance. But, of course, we had no money for this deposit. Without a second thought, Ammi immediately went to the jeweller and pawned her ornaments to pay the fees.

My education was her biggest priority. Abbu never interfered; he was too busy with his own struggles. He was just aware that his children were getting their education. So this became a sort of a ritual. Every time I needed money for my education, she would deposit her jewellery as a collateral and take a loan. Then after some months, when some money had been saved up, she would go get her jewellery back. Being the oldest, I experienced her qurbaniyan first-hand. The rest of the kids were quite small, so I am not sure if they remember this sacrifice. It also set a precedent for my siblings to focus on their education no matter what.

To Order The Book Click An Ordinary Life: A Memoir By Nawazuddin Siddiqui